Shabana is set apart by her subtlety, emotional depth, and incredible range as an actor, writes Deepa Gahlot

It’s gone down in movie lore. On hearing that ad filmmaker Shyam Benegal was casting for his feature film, Shabana Azmi, glammed up and went to meet him. She was unaware that the role was for a poor village woman in Ankur (1974). The cinematographer Govind Nihalani was unimpressed, but Benegal cast her, and turned her into Laxmi of his film. Thence began the saga of a long and illustrious career, with Shabana, turning 75 on September 18, 2025, becoming a respected star in India and abroad, with too many awards and accolades to count.

She jocularly narrates her mother, Shaukat Kaifi’s comment, that a director who cast her in that role must be a fraud. (Later, when she saw the film, she also applauded the loudest.) But Ankur was also the beginning of a significant collaboration between director and performer, and she went on to star in many of Benegal’s films, like Nishant (1975), Junoon (1978), Susman (1978), Mandi (1983), Antarnaad (1992).

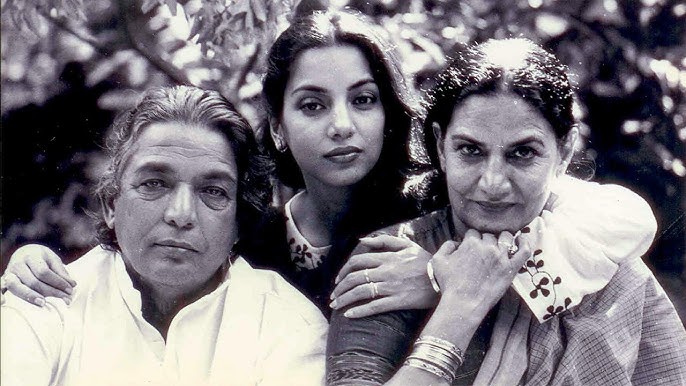

For an actress, who, as a daughter of intellectual and left leaning parents, Kaifi Azmi and Shaukat Kaifi, with training at the Film and Television Institute, one fallout of working with the stalwarts of the parallel cinema movement was that she also became a vocal activist for social change. Her hunger strike, in 1985, for the rights of slum dwellers is still remembered with awe—actors might sometimes speak up or march for a cause, but hardly anyone has had the courage to challenge the political establishment like this. She actively participated in protests against slum demolitions in Mumbai. She joined the Nivara Hakk (Right to Shelter) movement, living among slum dwellers to understand their daily struggles. It was a bold move that brought her face-to-face with the harsh realities of poverty and urban displacement. She recounts an instance when a minister asked her why she, a famous actress, was meddling in politics. Her response was, “I am an Indian citizen first, and an actress second. My work as an actress gives me a platform, and it is my duty to use it for those who do not have a voice.”

Her early years were spent in one room in a Mumbai commune, Red Flag Hall, where her parents lived alongside other one leftist and progressive writers, poets and artistes, so her understanding of life is not superficial, and that shows in her work—both as an actress and activist. She often recounts how their home was a hub for literary and political discussions, with luminaries like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Ali Sardar Jafri, Josh Malihabadi attending these gatherings. Her father instilled in her the belief that art must be rooted in reality, and this laid the groundwork for her future as an actor-activist. Her husband Javed Akhtar shares her beliefs and they are both vociferous in their views on social justice.

She has acted in commercial films like Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), but she has mentioned in interviews that after doing a film like Gautam Ghose’s Paar, in which she was exposed to extreme poverty, she automatically chose meaningful films down the years. Her career, spanning over five decades, has been a masterclass in the art of authentic storytelling, where each role is not just a performance but a conversation starter on the human condition.

She has mentioned in interviews that when she was reluctant to accept Amar Akbar Anthony, her father advised her, “Why don’t you do a film that the common people will watch? Then when they come to see you in a commercial film, they might also be inspired to see one of your parallel films.” That pragmatic view has stood her in good stead over the years, as is seen in the recent Rocky Aur Rani Ki Prem Kahani, in which she was paired with Dharmendra and even shared a kiss with him.

Her transformation for Ankur perfectly captures her commitment to her craft. The film was shot in a real village, and to prepare for her role, Shabana insisted on living there to understand the daily lives of the villagers. She would spend her days talking to the women, observing their mannerisms, and internalizing their struggles. This immersion was a fundamental part of her process, a practice she would continue throughout her career.

Caption – From Mandi to Khandhar, Shabana’s preparation for her roles, sets her apart

In Mandi, she played the overweight madame of a brothel and put on weight to play the character with an authenticity that challenged stereotypes. The film, a satire on politics and morality, was another testament to her willingness to tackle complex, socially relevant subjects. Immediately after, for Khandhar, she slimmed down drastically to get the haunted look of the lonely woman she played in the film. For every role, her preparation and understanding of the character is what makes her performances stand out.

Ankur won her the first of her five National Awards. In a record that’s impossible to match, she won National Awards for Arth, Khandhar and Paar; three years in a row, and the last for Godmother.

Her roles in these award-winning and memorable films demonstrated early on in her career, her subtlety, emotional depth, and incredible range.

In Arth, the semi-autobiographical film by Mahesh Bhatt, she played Pooja, who discovers her husband’s infidelity and decides to walk out of the marriage and forge her own path. Her performance resonated with millions, as she navigated the emotional turmoil of betrayal and the quiet strength of self-reliance. She often recalls how her own upbringing, where her mother’s financial independence was a given, helped her understand Pooja’s journey. She has said in interviews that while most men are defined by their careers, a woman’s worth is often tied to her roles as a wife or mother. Playing Pooja, who breaks this mould, was a deeply personal and liberating experience. She also mentions the drunken scene in which she confronts her husband’s girlfriend, as one that was emotionally draining, for a woman to ignore shame and fear of society to lash out with pain in full view.

In Khandhar directed by Mrinal Sen, she played a woman trapped in a decaying mansion, waiting for her fiancé who has long abandoned her. Her performance was a study in stillness, repressed desire and silent despair.

Caption: Swimming with pigs in Paar: one of the most iconic scenes in Indian cinema

In Paar by Gautam Ghose, she and Naseeruddin Shah played a poor couple fleeing their village after a violent confrontation. The climax, where they must swim across a river with a herd of pigs, is one of the most iconic scenes in Indian cinema. Shabana, despite her initial apprehension about the pigs, committed fully to the scene, her visceral performance capturing the raw desperation of their situation.

Her willingness to experiment led to international projects as well. Her role as a middle class housewife entering into a lesbian relationship with her younger sister-in-law (played by Nandita Das) in Deepa Mehta’s controversial film Fire (1996) was a courageous move that challenged social norms and brought her a new wave of admiration. The film, which was met with protests and censorship, solidified her reputation as an artiste who would not shy away from confronting uncomfortable truths. She often speaks of the vitriol she faced but also the support she received from those who believed in her message of inclusivity.

Inspired by her father’s involvement at the grassroots level in his native village, she carries on the work with the Mijwan Welfare Society, an NGO founded by her father. The organization works for the empowerment of the girl child in rural India. She is deeply passionate about this cause, ensuring that the legacy of her father’s vision lives on. She often speaks of how the delicate art of “chikankari” embroidery practiced by the village women, brought to the forefront by designers like

Manish Malhotra, has not only provided them with a livelihood but also with a sense of dignity and self-worth.

Shabana Azmi has also been a vocal advocate for communal harmony, HIV/AIDS awareness, and gender equality. In a recent interview, she reflected on her life and career, stating, “I grew up in a household where the lines between art and life were blurred. My father used to say that if you want to be a good artiste, you have to be a good human being first. I have tried to live by that principle.”