Deepa Gahlot throws light on a less-successful Balraj Sahni starrer about the plight of farmers

Dharti Ke Lal (1946)

As the farmers’ stir rocks our country, and draws attention to the men and women who slog to put food on our tables, it is worth watching a film that portrayed the plight of farmers, made by a man whose writing and cinema was always socially and politically aware—Khwaja Ahmad Abbas.

As the farmers’ stir rocks our country, and draws attention to the men and women who slog to put food on our tables, it is worth watching a film that portrayed the plight of farmers, made by a man whose writing and cinema was always socially and politically aware—Khwaja Ahmad Abbas.

Dharti Ke Lal (1946), co-scripted by Abbas and Bijon Bhattacharya, based on a play, Nabanna, by the latter and a story, Annadaata by Kishan Chander, the film predated Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zamin (1953), which is also about the calamity befalling a farmer, and is credited with heralding neo-realism in Indian cinema. Balraj Sahni was the common factor in both films.

It was Abbas’s first film as director, and he had the courage to show the audience poverty and suffering of the farmer, crushed under the manmade Bengal famine of 1943 in which five million people reportedly died of hunger.

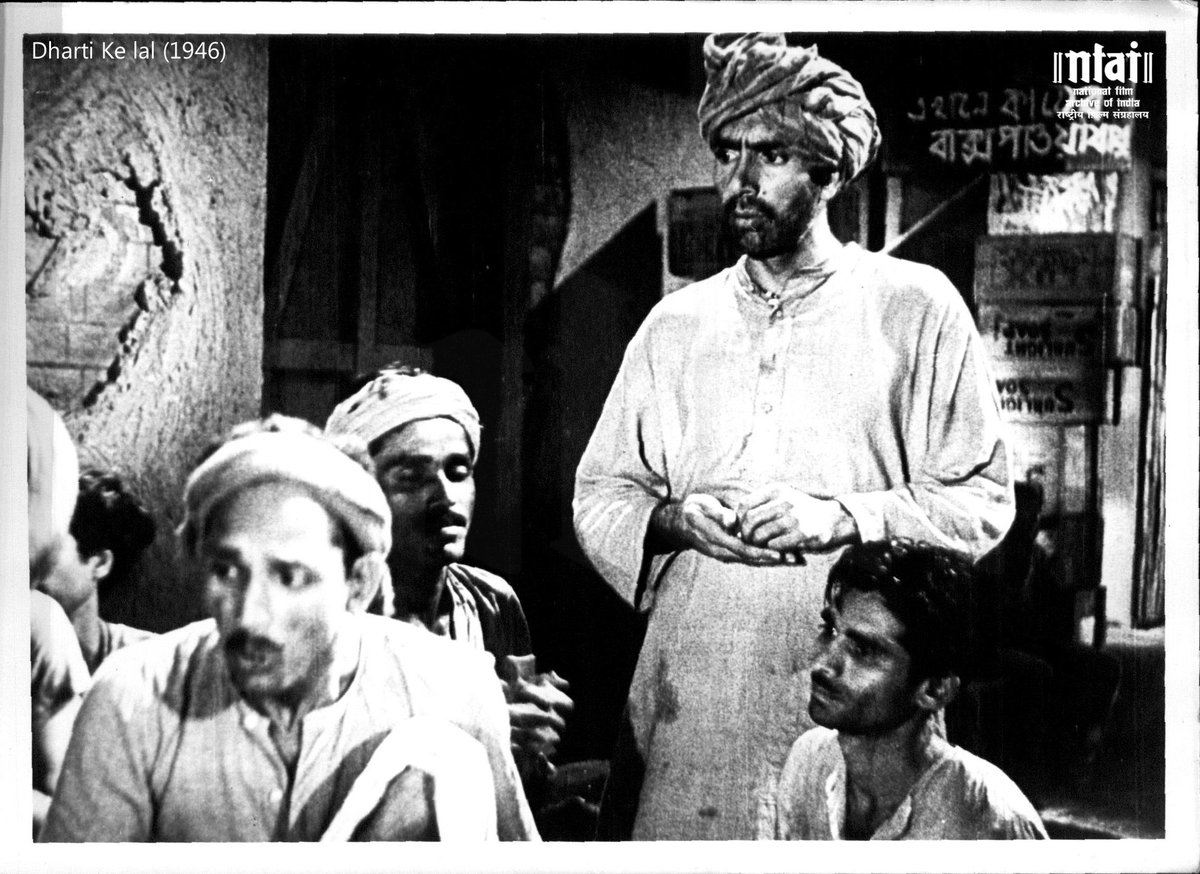

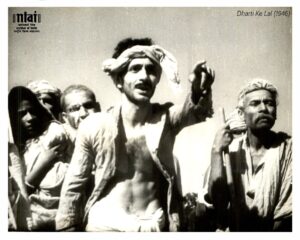

The film was produced by the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), the group of activists who reached out all over India with their plays reflecting the reality of the underprivileged. That explained the presence of IPTA members Sahni, Bengal’s theatre legends Sombhu and Tripti Mitra and Zohra Sehgal in the list of actors. Along with professional actors, Abbas had cast real farmers and workers, who brought to the screen a rare power, that made up for the rawness of the filmmaker and its stagey look.

The film was produced by the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), the group of activists who reached out all over India with their plays reflecting the reality of the underprivileged. That explained the presence of IPTA members Sahni, Bengal’s theatre legends Sombhu and Tripti Mitra and Zohra Sehgal in the list of actors. Along with professional actors, Abbas had cast real farmers and workers, who brought to the screen a rare power, that made up for the rawness of the filmmaker and its stagey look.

Dharti Ke Lal, is set during World War II, when the poor farmer was pitted against cruel zamindars, greedy moneylenders and an apathetic urban population, not to mention the indifferent British rulers of the time. Starving in their villages, the farmers moved to cities, where their misery was multiplied, and hungry people dropped dead in the streets. The opening of the film, with a boat sailing over calm waters (with Ravi Shankar’s music as accompaniment) plays to the city person’s mental picture of a bucolic rural setting. The actual horror of village life hits later.

In the fictional village of Aminpur in Bengal, Samaddar Pradhan (Sombhu Mitra) lives with his wife (Usha Dutt), elder son Niranjan (Balraj Sahni), elder daughter-in-law Binodini (Damayanti, Balraj Sahni’s real-life spouse) and younger son Ramu (Anwar Mirza).

To pay for Ramu’s wedding to Radhika (Tripti Mitra), Pradhan sells his stock of grains to the avaricious Kalijan Mahajan, who is hoarding rations to sell at high prices in the black market. Soon, there is a food scarcity in the village, while Mahajan’s granary is full.

Pradhan’s family gets into debt with Mahajan, promising him their next harvest and putting their thumb impressions on ledgers they cannot read, in effect signing off their lives to him. When Ramu’s baby is born, and there is no food in the house, the family loses its cow to the zamindar for not paying their lagaan. Ramu wants his father and brother to sell their land and they angrily tell him that they cannot sell their mother. He decides to try his luck in the city. When others in the village start dying, there is an exodus of the survivors to Calcutta—including the Pradhan family– where they end up begging and scavenging for scraps, while the rich feast in their mansions.

Communal discord rears its head in times of despair. Ramu loses his job as a rickshaw puller and turns to alcohol. Radhika is forced to prostitute herself in exchange for milk for her child, which is stolen by her mother-in-law, mad with hunger. A helpless Niranjan can only watch his father dying and his family disintegrating. He finds help and encouragement from a relief worker, Shambhu (Mahendra Nath), which gives him the courage to make a plea for collective farming to others like himself.

In the city, a desperate Ramu tries pimping and is aghast to find that the woman he is striking a deal for is his own wife. Niranjan and some other villagers return to Aminpur. He rallies other farmers to work hard and aim for a bumper harvest that will rescue them from their abject poverty. Ramu and Radhika, who have been cut off from their roots by their guilt and shame, can only watch wistfully from afar.

In the city, a desperate Ramu tries pimping and is aghast to find that the woman he is striking a deal for is his own wife. Niranjan and some other villagers return to Aminpur. He rallies other farmers to work hard and aim for a bumper harvest that will rescue them from their abject poverty. Ramu and Radhika, who have been cut off from their roots by their guilt and shame, can only watch wistfully from afar.

Despite the stark realism of the narrative, Abbas used songs to underline the emotions—Bhookha Hai Bengal, Ab Na Zabaan Pe Taale Dalo, Bitey Ho Sukh Ke Din and others—not popular numbers, but apt in the film.

The film won awards, was hailed by critics in India and abroad. It did not do well at the box-office; sadly, communal riots broke out when it was released and wrecked its already shaky commercial prospects. But it remains an important film—one of the few that documented a forgotten Indian tragedy.