Set in the Muslim populated area of Mumbai—the old buildings with a sense of community, where everybody minds everybody’s business, and speak a slang-y language that is peculiar to Mumbai (including the tendency of pluralizing random words). Jasmeet K. Reen’s debut film as director sounds and looks (and would smell, if it could) like Mumbai, and the characters have that snappy get-on-with-it attitude that belongs to this city.

Badru (Alia Bhatt) had a “love marriage” with Hamza (Vijay Varma) and became that sad cliché, the battered wife. Ticket collector Hamza hates his job and his awful boss (Kiran Karmarkar), which gives him an excuse to drink and beat up Badru at the slightest provocation. The neighbours hear the sounds, shake their heads and go back to whatever they were doing. Domestic violence has been normalised to such an extent, that nobody interferes. Badru’s mother, Shamsu (Shefali Shah) tries to get her daughter to leave her husband and make that short crossing across the courtyard where she lives.

However, Badru is always placated by her husband’s “Darlings” and gifts of cheap trinkets. Shamsu’s husband vanished years ago, and she runs a tiffin-supply business, which she hopes to expand through social media. The other men who play significant roles in the lives of the two women are the neighbourhood butcher Kasim (Rajesh Sharma) and Zulfi (Roshan Mathew), an aspiring writer and peddler of secondhand goods, who is infatuated with Shamsu.

The first half of the film, in which nothing really happens, except an introduction of the characters and their place in that small corner of Mumbai, that is about to change with the entry of a developer. When Badru’s plight does reach the cynical cops (Vijay Maurya and Santosh Juvekar), they are almost eager to file a complaint, hoping that for once a woman will have the courage to report her husband’s violence. To their disappointment, she withdraws it.

However, it is a standard worm-turns plot (scripted by Reen and Parveez Shaikh), and Badru is pushed beyond endurance one day, and along with her mother, concocts a plot to regain her respect, as she says. It is when Darlings attempts to be funny that it starts faltering and also trivializes the issue of violence against women. Perhaps without even being aware of it, the film endorses the misconceptions that women are directly (shoddily prepared food) or indirectly (allowing the beating) responsible for spousal abuse. As the mother-daughter thrash about trying to subdue the obnoxious Hamza, the film’s inability to balance its serious theme with comedy becomes glaringly evident.

If Darlings is still watchable, it is because the acting is uniformly excellent; Shefali Shah and Alia Bhatt have that rapport that allows them to communicate with their eyes—a mother like Shamsu, who wants her daughter to be rid of that brute of a husband is rare in Hindi films; mostly they are shown telling their daughters to make their marriage work.

For Mumbai residents, the look of the working class Muslim homes is perfectly recreated—that mix of antique furniture and new gadgets. It is not a part of the film, but Darlings unwittingly captures the gentrification of an area that will replace human connections with swimming pools and spas. There is no guarantee, however, that the women will be spared the indignity of domestic violence in those new high-rise towers.

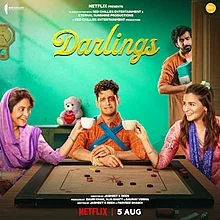

Darlings

Directed by: Jasmeet K. Reen

Cast: Alia Bhatt. Shefali Shah, Vijay Varma, Roshan Mathew and others

On Netflix