Discovering Japan, one bite at a time. By Vandana Kanoria

In her gorgeous essay ‘In Praise of the Cooks’, Midori Snyder says, “The very best of cooks are sorcerers, wizards, shamans and tricksters. They must be, for they are capable of powerful acts of transformation. All manner of life, mammal, aquatic, vegetable, seeds and nuts pass through their hands and are transformed by spells — some secret, some written in books annotated with splashes of grease and broth.”

Traditional Japanese cuisine, or Washoku, is one of the only three national food traditions recognised by the UN for its cultural significance. Tokyo was added to the Michelin Guide in 2007 and has since blazed forth, becoming the most-starred city in the world with 234 places listed in 2018.

The depth and variety of the deliciousness of Tokyo’s culinary world can be summed up in one word – Shokunin. Fresh and delicate, whilst there is simplicity about the food, one realises while eating how much details matter.

An 80-year-old tempura man who has spent six decades discovering the subtle differences yielded by temperature and motion; the 12-generation yakitori sage who uses metal skewers like an acupuncturist uses needles; the young man who has grown old at his father’s side, measuring his age in kitchen lessons, will know exactly what to do when it is his turn to be the master. This is Shokunin, or specialisation — artisans deeply dedicated to their craft. It is at the core of Japanese culture, as are ingredient obsession, technical precision and thousands of years of meticulous refinement. The most famous Shokunin is of course Jiro Ono, immortalised in the film Jiro Dreams of Sushi.

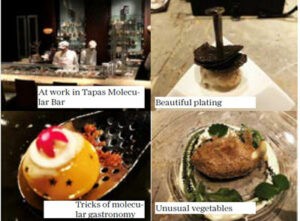

Tapas Molecular Bar

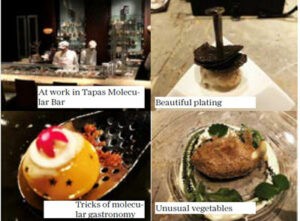

Don’t expect a typical night at Tapas Molecular Bar. From the moment you are seated, you enter the creative realm of highly entertaining food theatre by chef Kento Ushikobu, who takes you on a culinary journey that feels part-science, part-magic, and is unbelievably delicious. A mysterious bandanna-wrapped black box contains tools with the bandanna serving as a napkin, the menu… inside the measuring tape! Deconstructed Japanese classics using seasonal ingredients, and oh yes… all vegetarian!!

Don’t expect a typical night at Tapas Molecular Bar. From the moment you are seated, you enter the creative realm of highly entertaining food theatre by chef Kento Ushikobu, who takes you on a culinary journey that feels part-science, part-magic, and is unbelievably delicious. A mysterious bandanna-wrapped black box contains tools with the bandanna serving as a napkin, the menu… inside the measuring tape! Deconstructed Japanese classics using seasonal ingredients, and oh yes… all vegetarian!!

The usual basics of molecular cuisine – sous-vide cooking, effervescent foams, chemistry-lab equipment – transform  things we eat as if by a wizard’s wand, conjuring, in unconventional ways, familiar ingredients. Master cooks are alchemists, turning gnarled root vegetables into delicate sea foam, hazelnuts into digestive liqueur, combining spices and chilies into a paste that burns and soothes at the same time. Dinner is interactive and inventive, full of surprises, as objects transform, liquid nitrogen floats across the counter, a mint meringue soaked in liquid nitrogen explodes in your mouth and the resultant smoke is exhaled out of the nostrils. Different tools like hammers and shovels are used to prepare and consume each dish. Although the experience – for an intimate group of just eight diners per seating – makes this Michelin-starred restaurant exclusive, the atmosphere is casual and comfortable. Chefs chat enthusiastically, explaining preparation techniques, concepts and stories behind each dish, satisfying our curiosity about this show of wizardry and whimsy.

things we eat as if by a wizard’s wand, conjuring, in unconventional ways, familiar ingredients. Master cooks are alchemists, turning gnarled root vegetables into delicate sea foam, hazelnuts into digestive liqueur, combining spices and chilies into a paste that burns and soothes at the same time. Dinner is interactive and inventive, full of surprises, as objects transform, liquid nitrogen floats across the counter, a mint meringue soaked in liquid nitrogen explodes in your mouth and the resultant smoke is exhaled out of the nostrils. Different tools like hammers and shovels are used to prepare and consume each dish. Although the experience – for an intimate group of just eight diners per seating – makes this Michelin-starred restaurant exclusive, the atmosphere is casual and comfortable. Chefs chat enthusiastically, explaining preparation techniques, concepts and stories behind each dish, satisfying our curiosity about this show of wizardry and whimsy.

Narisawa

Narisawa and his groundbreaking cuisine at his iconic restaurant, has become a must do for visiting gastronomes. Narisawa melds classical French gastronomy with Japanese principles, local ingredients and molecular techniques. Taro potatoes from Ishikawa, lotus root from Hokkaido, strawberry and yame matcha from Fukuoka, are just some of the ingredients in the deliciously rich fourteen-course omakase vegetarian menu. Responding to seasons and landscape, his recipes are ground breaking, especially the ‘Satoyama Scenery and Essence of the Forest’, an elaborate edible landscape, evoking the forests and fields of rural Japan. The ‘Soil Soup’ which is, to quote him, “a dish that contains my conviction for a natural environment so safe, you can eat the soil itself.” Combining the deep, earthy flavor of actual soil from the pristine mountains of Nagano Prefecture, the food is “beneficial to both body and spirit and a continuously sustainable environment which we call Innovative Satoyama Cuisine.”

Narisawa and his groundbreaking cuisine at his iconic restaurant, has become a must do for visiting gastronomes. Narisawa melds classical French gastronomy with Japanese principles, local ingredients and molecular techniques. Taro potatoes from Ishikawa, lotus root from Hokkaido, strawberry and yame matcha from Fukuoka, are just some of the ingredients in the deliciously rich fourteen-course omakase vegetarian menu. Responding to seasons and landscape, his recipes are ground breaking, especially the ‘Satoyama Scenery and Essence of the Forest’, an elaborate edible landscape, evoking the forests and fields of rural Japan. The ‘Soil Soup’ which is, to quote him, “a dish that contains my conviction for a natural environment so safe, you can eat the soil itself.” Combining the deep, earthy flavor of actual soil from the pristine mountains of Nagano Prefecture, the food is “beneficial to both body and spirit and a continuously sustainable environment which we call Innovative Satoyama Cuisine.”

Hajime

“Pay homage to nature” says Hajime.

Universe, harmony, circulation, life and love describe the chef ’s culinary philosophy. His greatest inspiration is the interconnectedness of things. Hajime has achieved three Michelin stars in the shortest period of time in the history of Michelin ratings.

Combining French classics with his Japanese heritage, Chef Hajime Yoneda is a meticulously skilled culinary master. Transitioning from being an electronic components designer to becoming a professional chef, he has an artist’s eye and a poet’s vision of the world. A painter, Hajime’s food is pure art. He is deeply affected by the equilibrium and harmony that exist in nature. The 2019 menu called Chikyu Tono Taiwa or ‘Dialogue with the Earth’, includes approximately seventeen dishes, some of which are evocatively called:

Life – cauliflower, black olive, tomato and rice;

Inshore – seaweed, sansho, hatcho miso, white kidney beans;

Mountain – rizoni, asparagus, broad beans, romanesco broccoli, green beans;

Assimilation and Destruction – avocado, Asian hazel, pumpkin, black pepper.

His reverence for nature is reflected in the most innovative and beautiful dish that I have ever seen or eaten. Called ‘Chikyu’ or Earth, it represents the cycle of life, and the reconstruction of the planet in miniature, through hundred and ten different vegetables, grains, herbs and sea foam. “Fallen leaves from the forest enrich the earth, and the nutrients flow into the sea,” he explains. His aim? To show a culinary story about nature and time. (pics 21-25)

Daigo

Nomura Yoshiko, who founded the two-Michelin-star Daigo in 1950, remained the

Okami, or lady of the establishment, until recently. Family run, the current Okami, Nomura Satoko, keeps the tradition of Japanese hospitality alive and Nomura Daisuke, the head chef, is one of her three sons.

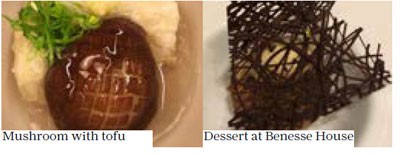

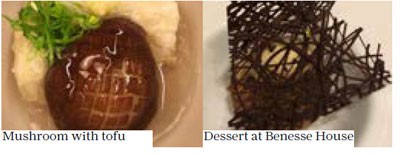

Seated in traditional style in one of the eight sparsely furnished private dining rooms, with a large glass window looking into a garden, we feasted on fifteen jaw-dropping, artistically crafted courses served Kaiseki style. From bite size nibbles, to a hearty bowl of soup with rice and mushrooms, each plate was decorated keeping in mind Buddhist principles and aesthetics. Ceramic dishes and lacquer bowls coordinated beautifully with food, heightening the sensory experience of eating and fulfilling Daigo’s mission to stimulate the five senses with each bite. Delicate bites of different tofu preparations – a Daigo speciality – soya, matcha and seasonal Japanese fruits and vegetables, are designed to allow the diner to appreciate the Tanmi or the subtlety of flavours, which progress from lighter to bolder, allowing you to savour the essence of each main ingredient. (pics 26, 27)

A vegetarian in Japan

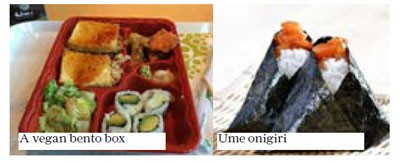

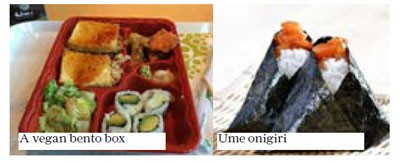

Someone once said Japan is a vegetarian paradise wrapped in a vegetarian hell! Being a vegetarian in Japan can be difficult, although, in recent years, thanks to apps such as Happy Cow, Tokyo Veg Guide, and Uber Eats finding meatless meals has become much easier. The ever-resourceful Google Translate helps to navigate the intricacies of the language. Courtesy JustHungry.com, a vegetarian/vegan can print a card stating a no meat, fish, dashi, egg meal for the waiter. A growing number of cafes and restaurants, including traditional Japanese ones, offer vegetarian options and English menus. Inconvenience stores and bakeries, vegan snacks like dried fruits, nuts, red bean pretzels, edamame rolls, black sesame and cheese bagels satisfy hunger pangs. As do the wonderfully flavourful Ume Onigiris, which are rice with plums wrapped in seaweed. Even Shinkansens or bullet trains serve vegan ekiben or bento boxes!

Kaiseki is the most elegant and extraordinary of all Japanese cuisine. Beautiful yet austere, ancient yet innovative, the ingredients are cooked or left raw, leading to a perfect balance of taste, texture, appearance and colour. The meals have moments of great beauty and taste. White miso with black sesame, foraged vegetables and herbs, a confounding variety of tofu, the sharp and sour pickled vegetables, are all served in heirloom lacquer bowls. Pine needles and fallen leaves cover grilled gingko nuts and sit on centuries old ceramic plates. Gohan, or rice is served with a simple splash of colour, sometimes hiding a nest of grilled wild mushroom, sometimes crisp, with herbs, served in its own broth with seasonal flowers.

It is easy for a vegetarian to feast on this awesomeness in Michelin starred restaurants and ryokans by simply emailing food preferences. The chefs are only too happy to stretch their culinary creativity.

Izakaya Yakitori and Shojin Ryori

Izakaya and Yakitori often have vegetarian options – brightly coloured root vegetables like daikon, yam, sweet potato, are grilled on sticks with mochi rice cakes. Tempura, which is actually a Portuguese import, uses seasonal and aromatic vegetables such as renkon or lotus, satsumaimo or sweet potato and sansai or wild mountain greens, which are a spring speciality.

The influence of Shojin Ryori – a traditional Buddhist vegetarian cuisine – is evident in modern Japanese food. Humble, yet elaborate, these meals grew around Buddhist temples. They feature seasonal, local vegetables and a mind-boggling variety of tofu, to create beautiful dishes using light cooking and preserving techniques. (pics 37-40)

Food, a love story

Eating good food, be it in a humble roadside shack, or in Michelin starred restaurants is a passion. Often our dates of travel are fixed around reservations in hard-to-get restaurants.

Add to this my deep love of Japan – its culture, its aesthetics, and the beautiful simplicity of everyday things. Travelling in Japan, I feel I am time travelling between the future and the past, between the ephemeral and the permanent. Centuries old Buddhist temples exist peace fully with current fads, be it cat cafes or robot restaurants. It is a place of contrasts – cherry blossoms and autumn leaves fall softly, and tsunamis rage and ravage the coasts. This reconciliation of opposites I felt most keenly while eating in Japan. Dishes, prepared using the most cutting edge technology, are served in traditional kaiseki feasts, often on heirloom plates and bowls. Local ingredients are interpreted, absorbing the latest in international food trends, creating something distinctively Japanese.

And with apologies to Ibn Battuta, Japanese gastronomy – it leaves you speechless, then turns you into a storyteller.

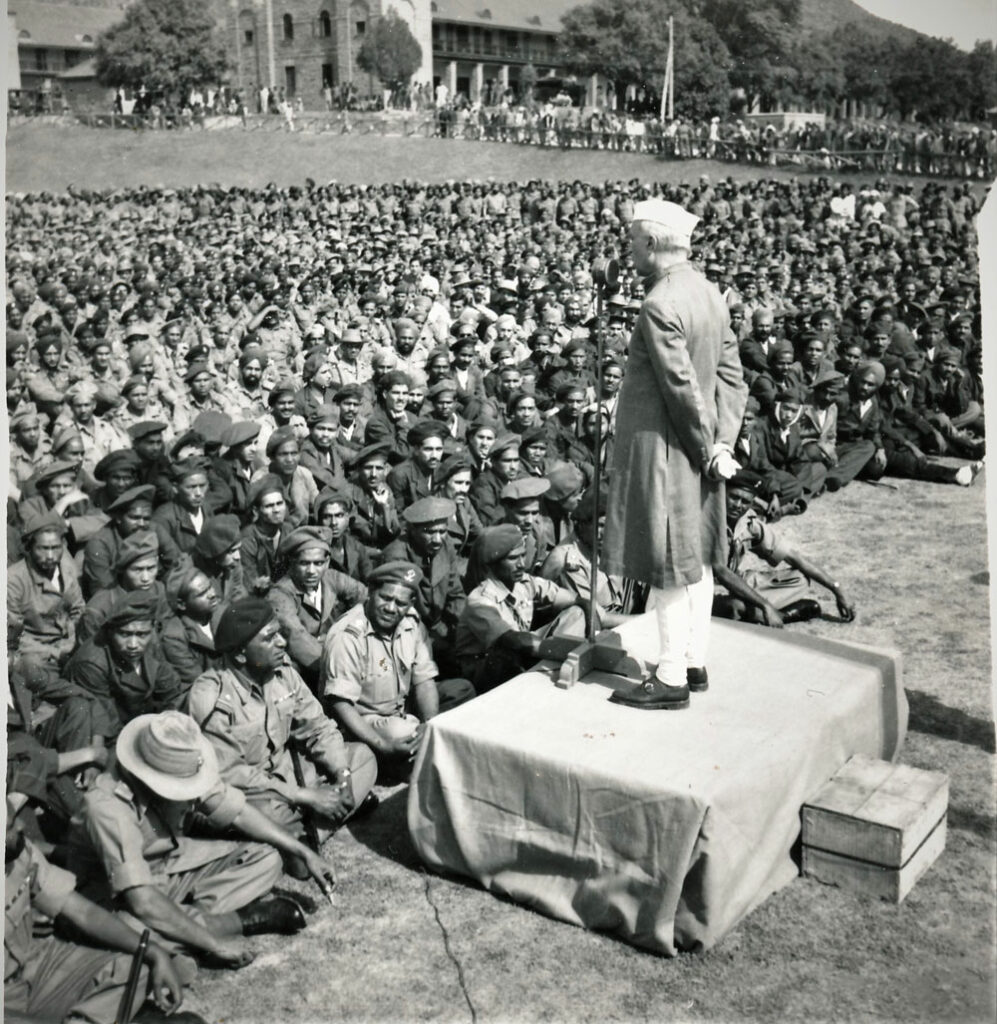

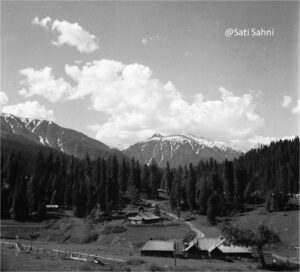

Sat Paul (Sati) Sahni, who was born in Rawalpindi in 1922,

participated in the Indian freedom struggle and later became

one of the few multimedia journalists of his generation.

He was a pioneer photojournalist, and worked for leading

international publications and news agencies. An

experienced war correspondent, he covered all the four major

wars India was involved in, and has written many

books – his last book was titled Nehru’s

Kashmir. He passed away in October 2010.

Sat Paul (Sati) Sahni, who was born in Rawalpindi in 1922,

participated in the Indian freedom struggle and later became

one of the few multimedia journalists of his generation.

He was a pioneer photojournalist, and worked for leading

international publications and news agencies. An

experienced war correspondent, he covered all the four major

wars India was involved in, and has written many

books – his last book was titled Nehru’s

Kashmir. He passed away in October 2010.

It is important to point out that the legality of Accession was not questioned at any time by the UN Security Council and the UN Commission for India & Pakistan, or any of its representatives or mediators like Dr Graham,

It is important to point out that the legality of Accession was not questioned at any time by the UN Security Council and the UN Commission for India & Pakistan, or any of its representatives or mediators like Dr Graham,

My first year of training began with Raag Bhairav. I had finished First Year at college and was into the intermediate science year. Music practically became my second, equally time-consuming, activity during that time. The lessons were regular, about three to four times a week. Tai started with me for fees of Rs. 50 per month, but in a couple of months, she stopped accepting any fees. Her reasoning was that she herself liked the challenge she faced while teaching me, to stay a step ahead of me, and that enriched her own music. So from then on she never accepted from me a single paisa for all the wealth of music she showered upon me!

My first year of training began with Raag Bhairav. I had finished First Year at college and was into the intermediate science year. Music practically became my second, equally time-consuming, activity during that time. The lessons were regular, about three to four times a week. Tai started with me for fees of Rs. 50 per month, but in a couple of months, she stopped accepting any fees. Her reasoning was that she herself liked the challenge she faced while teaching me, to stay a step ahead of me, and that enriched her own music. So from then on she never accepted from me a single paisa for all the wealth of music she showered upon me!

Don’t expect a typical night at Tapas Molecular Bar. From the moment you are seated, you enter the creative realm of highly entertaining food theatre by chef Kento Ushikobu, who takes you on a culinary journey that feels part-science, part-magic, and is unbelievably delicious. A mysterious bandanna-wrapped black box contains tools with the bandanna serving as a napkin, the menu… inside the measuring tape! Deconstructed Japanese classics using seasonal ingredients, and oh yes… all vegetarian!!

Don’t expect a typical night at Tapas Molecular Bar. From the moment you are seated, you enter the creative realm of highly entertaining food theatre by chef Kento Ushikobu, who takes you on a culinary journey that feels part-science, part-magic, and is unbelievably delicious. A mysterious bandanna-wrapped black box contains tools with the bandanna serving as a napkin, the menu… inside the measuring tape! Deconstructed Japanese classics using seasonal ingredients, and oh yes… all vegetarian!! things we eat as if by a wizard’s wand, conjuring, in unconventional ways, familiar ingredients. Master cooks are alchemists, turning gnarled root vegetables into delicate sea foam, hazelnuts into digestive liqueur, combining spices and chilies into a paste that burns and soothes at the same time. Dinner is interactive and inventive, full of surprises, as objects transform, liquid nitrogen floats across the counter, a mint meringue soaked in liquid nitrogen explodes in your mouth and the resultant smoke is exhaled out of the nostrils. Different tools like hammers and shovels are used to prepare and consume each dish. Although the experience – for an intimate group of just eight diners per seating – makes this Michelin-starred restaurant exclusive, the atmosphere is casual and comfortable. Chefs chat enthusiastically, explaining preparation techniques, concepts and stories behind each dish, satisfying our curiosity about this show of wizardry and whimsy.

things we eat as if by a wizard’s wand, conjuring, in unconventional ways, familiar ingredients. Master cooks are alchemists, turning gnarled root vegetables into delicate sea foam, hazelnuts into digestive liqueur, combining spices and chilies into a paste that burns and soothes at the same time. Dinner is interactive and inventive, full of surprises, as objects transform, liquid nitrogen floats across the counter, a mint meringue soaked in liquid nitrogen explodes in your mouth and the resultant smoke is exhaled out of the nostrils. Different tools like hammers and shovels are used to prepare and consume each dish. Although the experience – for an intimate group of just eight diners per seating – makes this Michelin-starred restaurant exclusive, the atmosphere is casual and comfortable. Chefs chat enthusiastically, explaining preparation techniques, concepts and stories behind each dish, satisfying our curiosity about this show of wizardry and whimsy. Narisawa and his groundbreaking cuisine at his iconic restaurant, has become a must do for visiting gastronomes. Narisawa melds classical French gastronomy with Japanese principles, local ingredients and molecular techniques. Taro potatoes from Ishikawa, lotus root from Hokkaido, strawberry and yame matcha from Fukuoka, are just some of the ingredients in the deliciously rich fourteen-course omakase vegetarian menu. Responding to seasons and landscape, his recipes are ground breaking, especially the ‘Satoyama Scenery and Essence of the Forest’, an elaborate edible landscape, evoking the forests and fields of rural Japan. The ‘Soil Soup’ which is, to quote him, “a dish that contains my conviction for a natural environment so safe, you can eat the soil itself.” Combining the deep, earthy flavor of actual soil from the pristine mountains of Nagano Prefecture, the food is “beneficial to both body and spirit and a continuously sustainable environment which we call Innovative Satoyama Cuisine.”

Narisawa and his groundbreaking cuisine at his iconic restaurant, has become a must do for visiting gastronomes. Narisawa melds classical French gastronomy with Japanese principles, local ingredients and molecular techniques. Taro potatoes from Ishikawa, lotus root from Hokkaido, strawberry and yame matcha from Fukuoka, are just some of the ingredients in the deliciously rich fourteen-course omakase vegetarian menu. Responding to seasons and landscape, his recipes are ground breaking, especially the ‘Satoyama Scenery and Essence of the Forest’, an elaborate edible landscape, evoking the forests and fields of rural Japan. The ‘Soil Soup’ which is, to quote him, “a dish that contains my conviction for a natural environment so safe, you can eat the soil itself.” Combining the deep, earthy flavor of actual soil from the pristine mountains of Nagano Prefecture, the food is “beneficial to both body and spirit and a continuously sustainable environment which we call Innovative Satoyama Cuisine.”

You don’t need a garden to do gardening. In a flat you have balconies, where you can grow multiple hanging baskets and pots. You don’t even have to buy baskets, you must be having old plastic colanders. Put coconut fibre all around or a fine mesh that you get from potato vendors.

You don’t need a garden to do gardening. In a flat you have balconies, where you can grow multiple hanging baskets and pots. You don’t even have to buy baskets, you must be having old plastic colanders. Put coconut fibre all around or a fine mesh that you get from potato vendors.

In the morning I see small colorful birds sitting on my plants, and I thank God for getting me interested in gardening.

In the morning I see small colorful birds sitting on my plants, and I thank God for getting me interested in gardening.

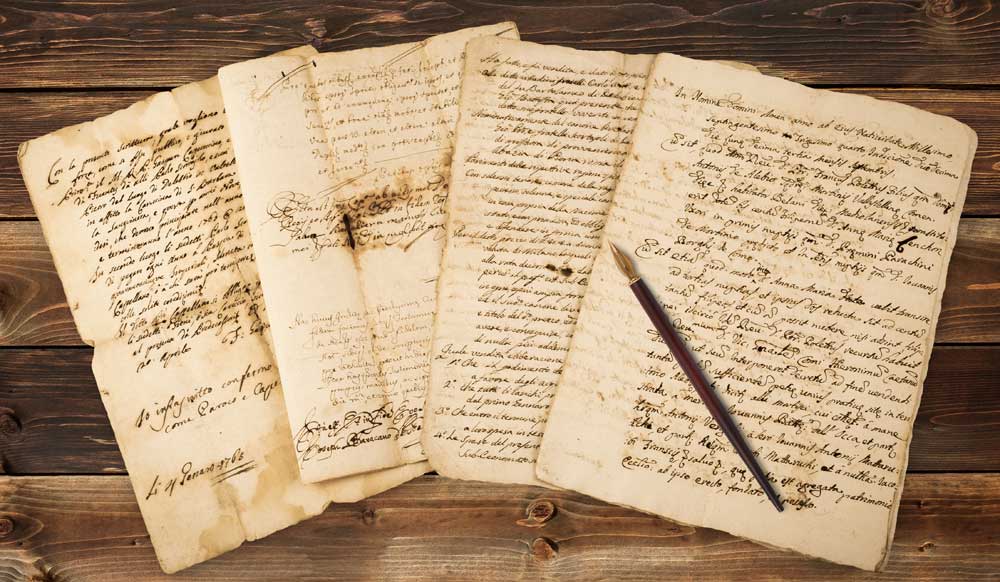

With increasing longevity, it is common today to find people suffering from terminal illnesses or from varying forms of dementia.Bodily functions decline and people are unable to care for themselves physically or to use their mental faculties. In such situations of total dependency and inability to take informed decisions for themselves, the one way by which a person can take his/her own decision regarding his/her treatment is by means of an “Advance Directive” or a “Living Will”. It is a document prepared in advance by a person, expressing his/her directions with regard to medical treatment in case of a situation of total dependency.

With increasing longevity, it is common today to find people suffering from terminal illnesses or from varying forms of dementia.Bodily functions decline and people are unable to care for themselves physically or to use their mental faculties. In such situations of total dependency and inability to take informed decisions for themselves, the one way by which a person can take his/her own decision regarding his/her treatment is by means of an “Advance Directive” or a “Living Will”. It is a document prepared in advance by a person, expressing his/her directions with regard to medical treatment in case of a situation of total dependency.