Without these magnificent people with their drive and ambition laying down the foundation of cinema, India would not have been the great centre of movie-making that it is today, writes Deepa Gahlot

The recent, much admired – and somewhat criticised—web series Jubilee, directed by Vikramaditya Motwane, has evoked some interest in the history of cinema, in a country so indifferent to the past, that Dadasaheb Phalke’s name is attached to a national award for lifetime achievement, but his home in Nashik is marked just by a plaque; anywhere else in the world, the Father of Indian Cinema would have a museum to his name. The man himself died in penury and oblivion.

Devika Rani and Himansu Rai, who inspired two of the lead characters in Jubilee, were cinema pioneers who heralded the Golden Age of Hindi films; their stardom and glamour ensured a place for them in movie history, but there are many others, who have been totally forgotten. A very large section of early Indian cinema has not even survived—the prints either sold to extract silver from the celluloid strips, or simply destroyed by neglect. Laboratory and storage facility fires took out another large chunk. If it was not for the tireless efforts of PK Nair who established the National Film Archives of India in Pune, even more of India’s film heritage would have been destroyed.

Phalke’s Raja Harishchandra (1913) is the first Indian feature film, but a year before that Dadasaheb Torne’s Shree Pundalik was released. It was just a recording of a stage play, so not really counted as a feature film.

According to information available on the net, Torne was the first Indian to open a movie distribution company. In 1929, he started Famous Pictures with his colleague Baburao Pai. He was the one who advised Ardeshir Irani to set up his own studio (Jyoti Studio, that is now just a board on a property full of motor garages) and film production companies, Imperial and Sagar. It is recorded in cinema history that Ardeshir Irani made the first Indian talkie, Alam Ara (1931). After a long and successful career, Torne died in obscurity and Irani, who combined creative talent with business acumen, surely needs to be remembered too, even if very few bits of Alam Ara remain.

While Bombay (now Mumbai) was the incubator of Indian cinema, films were being made in Bengali, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Assamese and Punjabi, soon after Raja Harishchandra. The first Tamil film was Keechaka Vadham (1917) by R. Nataraja Mudaliar, the first Malayalam film, Vigathakumaram (1928) was made by JC Daniel Nadar; the first Telugu film was Savitri (1933) directed by C. Pullaiah. Jyoti Prasad Agarwala made Joymoti (1935), the first Assamese film. The first film studio in South India, Durga Cinetone, was built in 1936 by Nidamarthi Surayya in Rajahmundry, Andhra Pradesh.

Before Partition, Lahore used to be a major film production centre too, with Dalsukh M. Pancholi as the pioneer, whose Pancholi Art Pics was the largest film studio in Lahore.

The first chain of Indian cinemas, Madan Theatres was established by Jamshedji Framji Madan, who was also behind the production and distribution of several early films.

In Mumbai, there was the legendary Bombay Talkies, set up by Devika Rani and Himansu Rai in 1934, but there were others gaining ground in those heady days of cinema. Calcutta’s (Now Kolkata) New Theatres founded in 1931 under the leadership of BN Sircar and between the two behemoths, they had captured the best writing, directing, music and acting talent, going on to make some of the biggest hits of the era. A decade later, after the death of Himansu Rai, Sashadhar Mukherjee, Rai Bahadur Chunilal, Ashok Kumar and Gyan Mukherjee left Bombay Talkies and set up Filmistan, continuing their winning streak. (The derelict Bombay Talkies property still stands in Malad, a Mumbai suburb, Filmistan in the nearby suburb of Goregaon has survived in much better shape.)

In 1929, Prabhat Films had been formed, first in Kolhapur and then shifted to Pune in 1933 where a sprawling studio was built (where the Film & Television Institute of India now stands) by V. Shantaram, VG Damle, Keshav Rao Dhaibar, S. Fatehlal and SV Kulkani. They made socially relevant films in Hindi and Marathi. Shantaram broke away to set up his Rajkamal Kalamandir in Mumbai, a part of which still stands.

In Madras (now Chennai), MN Swamy and BN Reddy’s Vauhini Studios. SS Vasan’s Gemini Studios and AV Meiyappan’s AVM Studios had captured the Southern market and later moved to Hindi cinema too.

JBH Wadia and his brother Homi under their banner Wadia Movietone, made a whole lot of mythological and stunt films, many of them starring ‘Fearless’ Nadia. Working with them in some of their hits was Babubhai Mistry, who could be called India’s first special effects wizard.

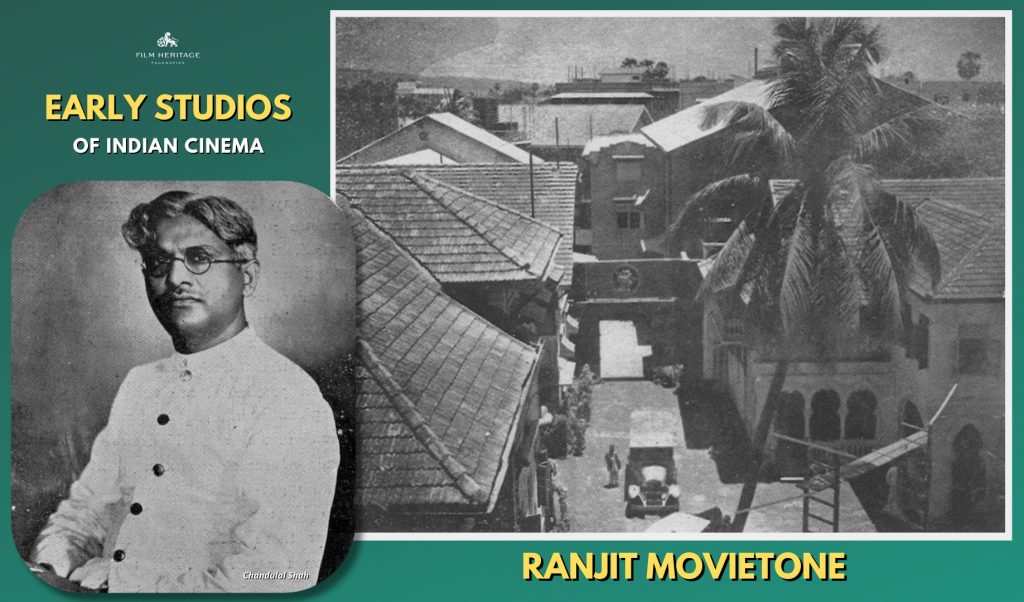

Chandulal Shah founded Ranjit Studios (it remains in dilapidated state, housing a rabbit warren of offices) and Ranjit Movietone, partnering with Gohar Mamajiwala, to make several successful films in the silent as well as talkie eras. Shah—the original Man In White Suits– was also a charismatic industry leader—the silver jubilee (1939) and golden jubilee of the Indian film Industry (1963) were celebrated under his guidance. He was the first president of the Film Federation of India. After a string of flops and gambling losses, Shah also died forgotten and in impoverished condition.

There were a few women too, whose contribution to cinema has been neglected—Saraswati Devi was the first female music composer; Very little is known about Fatma Begum, the first female film director, who was also writer, actress and producer. She launched her own production house, Fatma Films, which later became Victoria-Fatma Films, and directed her first film, Bulbul-e-Paristan, in 1926. Then there was the formidable Jaddanbai, who started as a singer, and went on to compose music, set up her own production company, Sangeet Films and launched the career of her daughter, Nargis.

To Sohrab Modi goes the credit for making some of the finest and most extravagant historical and costume dramas. He made India’s first Technicolour film, Jhansi Ki Rani (1953), though the first colour film was Mehboob Khan’s Aan (1952), which was shot in Gevacolour and blown up to Technicolour. The first indigenously made colour film, however, was, directed by Moti B. Gidwani and produced by Ardeshir Irani, based on a novel by Saadat Hasan Manto (whose experiences in the world of films have been documented in many essays and stories).

There are of course, many more names, all having contributed to the huge movie industry in India. What Jubilee got right was the passion of these pioneers—they were dreamers, creators, nurturers of talent first, businessmen later. They envisaged movies as entertainment, but also a means of social progress. Except for a few, whose work has been documented in books and research papers, they have been lost to time, but without these magnificent men with their drive and ambition laying down the foundation of cinema, India would not have been the great centre of movie-making that it is today.