Artist Angeli Sowani shares the stories and celebrates the unsung Indian heroes of World War I

“For God’s sake don’t come, don’t come, don’t come….”

This is the story of a million Indian soldiers who joined in the efforts of the Great War, 74,000 of whom died. Of the men that crossed the KaloPani—‘thinking he was going to Vilayat after all, England, the glamorous land of his dreams, where the sahibs came from, where people wore coats and pantaloons and led active fashionable lives.’

The Trigger

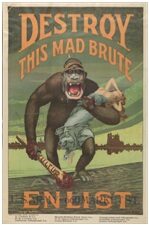

On June 28, 1914 Archduke Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was assassinated. Two months later, Britain declared war on Germany. But the impact of this war would echo far beyond the shores of Europe, throwing into its mix soldiers and countries from across the World – this was a war of Empires.

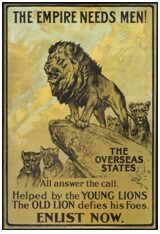

The Empire needs men!

Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy of India announced that India was at war too. This was done without consulting any of the Indian political leaders of that time. One of the reasons for the Indian political parties to go along with this, was that they would surely get a better deal for Independence, once the war was over.

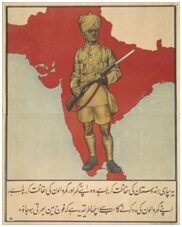

Once the wheels of War started moving, so did the fundraising and recruitment of soldiers in accordance with the theory of “martial races”: the categorisation, by the British, of people into those that were considered typically brave and well-built for fighting, and those that were not. Recruited soldiers came from the Punjab, Northwest Frontier, and the hills of the Himalayas. In these areas, nearly 40% of all young men enlisted.

Early in the war, young men were enthused to enlist through propaganda posters and fairs held in rural villages.

Recruitment songs blared out:

“Here you get shoes, there you will get boots!

Get enlisted!

Here you get torn rags, there you will get suits!

Get enlisted!

Here you get dry bread, there you’ll get biscuit!

Get enlisted!

Here you’ll have to struggle, there you will get salutes

Get enlisted!”

While early recruitment focused on building a sense of glory, by 1917 a quota system had been put in place where each province had to provide a certain number of soldiers. Sometimes aggression was used, and it did spark off riots in some areas.

In the Punjab, women would sometimes follow their men, pleading with them not to go. They even threw stones at the recruiters, and used their songs to mark their anger:

War destroys towns and ports, it destroys huts

I shed tears, come and speak to me

All birds, all smiles have vanished

And the boats sunk

Graves devour our flesh and blood

By the end of the war it is estimated that India, “the Jewel in the Crown” had provided over a million Indian combatant and non-combatant soldiers, 1,70,000 animals and £121.5 million (about £8.5 billion today) in funding to the war effort.

Across the Kalo Pani

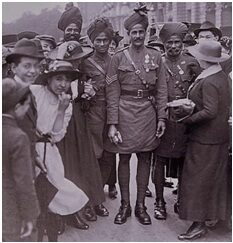

Early morning, on the 26th of September 1914, as the sun was rising over Marseilles, ships carrying the first Indian Soldiers – from the Lahore Division- sailed into the harbor. As the anchor was dropped the soldiers, seasick and pale after the journey, appeared on the ship’s deck.

‘Marsels!’

‘We have reached Marsels!’

‘Hip Hip Hurrah!’

The sepoys were shouting excitedly on the deck…

The King-Emperor, too, had sent them a message… congratulating them on their personal devotion to his throne, and assuring them how their one-voiced demand to be foremost in the conflict had touched his heart”

Massia Bibikoff, a Russian Artist, was in Marseille to sketch the arrival of the troops; in her words, “There was not one less than five feet eleven in height, slender, beautifully proportioned…it was a delirious scene. People who were drinking in the cafes stood up and shouted “Vive L’Angleterre! Vivent Les Hindous! Vivent Les Allies!”

According to Santanu Das, a prominent World War 1 historian, “no army was so hotly pursued by the imperial paparazzi.”

Into the fray

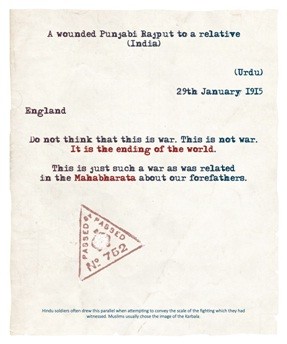

Of course, the brutality of war in the trenches soon banished any illusions of glory, as a letter home by one of the soldiers poignantly illustrates:

“… For God’s sake, don’t come, don’t come, don’t come to this war in Europe. Cannons, machine guns, rifles and bombs are going day and night, just like the rains in the month of Sawan. Those who have escaped so far are like the few grains left uncooked in a pot.”

In total 74,000 soldiers from the Indian Subcontinent were killed in the Great War, and thousands more brutally wounded and mentally damaged. But from this darkness, stories of bravery emerged.

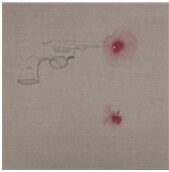

In 2019, I put together an exhibition at the Jehangir Gallery, called “Medals and Bullets”, commemorating the 100th anniversary of the end of the war. The exhibition focused on the eleven Indian men who were awarded the Victoria Cross in the Great War, along with photographs, films and excerpts of the countless letters that were written home sharing the true experience of war.

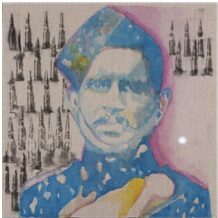

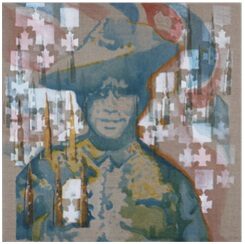

What follows are portraits I painted of four of these Victoria Cross holders, together with press articles written about them at the time.

DAFADAR GOBIND SINGH VC – “THE HORSEMAN”

London Gazette, 11 January 1918

Gobind Singh, Lance-Dafadar… awarded the Victoria Cross for most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty in thrice volunteering to carry messages between the regiment and the Brigade Headquarters, a distance of one and a half miles over open ground, which was under observation and heavy fire of the enemy. He succeeded in each time delivering his message, although on each occasion his horse was shot and he was compelled to finish the journey on foot. Dafadar Gobind Singh was present at Buckingham Palace at his investiture.

NAICK DARWAN SING NEGI VC – “INVINCIBLE”

Extract from the Gazette of India: Army Department, Delhi, 15 Jan. 1915, Indian Army.

“His Majesty the King-Emperor has been graciously pleased to approve the grant of the Victoria Cross for conspicuous bravery while serving to No. 1909, Naick Darwan Sing Negi, 1st Battalion, 39th Garhwal Rifles. For great gallantry on the night of 23-24 Nov., Festubert, France, when the regiment was engaged in retaking and clearing the enemy out of our trenches, and, although wounded in two places in the head, and also in the arm, being one of the first to push round each successive traverse, in the face of severe fire from bombs and rifles at the closest range”

INDRA LAL ROY – “LADDIE”

2 December 1898 – 22 July 1918

Indra Lal Roy was the sole Indian World War I flying ace. At a time when the British did not consider Indians to be capable of even running their own country, Roy broke through the colour and race barrier to become an officer and fighter pilot in the Royal Flying Corps – the elite of the elite.

In the course of 13 days between July 6th and July 19th, 1918 Roy claimed ten aerial victories; five aircraft destroyed and five ‘down out of control’; in just over 170 hours of flying time. He was shot down on the Western Front over France on July 22nd 1918 and was buried with full military honours in France by the Germans.

Roy was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross – the first Indian to receive this honour. The citation in the London Gazette on 21st September 1918 praised Roy as ‘a very gallant and determined officer whose remarkable skill and daring had on one occasion enabled him to shoot down two enemy machines in one patrol’.

RIFLEMAN KARANBAHADUR RANA VC – “THE LEVELHEADED RIFLE”

London Gazette, 21 June 1918

“Karanbahadur Rana, No. 4146, Rifleman, 2/3rd Battn. Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles.For most conspicuous bravery, resource in action under adverse conditions, and utter contempt for danger. During an attack he, with a few other men, succeeded under intense fire in creeping forward with a Lewis gun, in order to engage an enemy machine gun which had caused severe casualties to officers and other ranks who had attempted to put it out of action. No.1 of the Lewis gun opened fire, and was shot immediately. Without a hesitation Rifleman Karanbahadur pushed the dead man off the gun, and in spite of bombs thrown at him and heavy fire from both flanks, he opened fire and knocked out the enemy machine-gun crew; then, switching his fire on to the enemy bombers and riflemen in front of him, he silenced their fire. He kept his gun in action and showed the greatest coolness in removing defects which on two occasions prevented the gun from firing.”

Naik Karanbahadur Rana was personally decorated with the Victoria Cross by His Majesty the King-Emperor.

A history forgotten, and remembered

Sarojini Naidu, the nationalist leader and poet, wrote in 1915:

“They lie with pale brows and brave,

Broken hands

They are strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance

On the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France”

This was meant to be “The war that ended all wars”. It was the first time in history that nations across the world had pitted themselves against one another, for the age-old reason for any disagreement: power. In all, 40 million people were killed or left injured, and 16 million animals lost their lives. World War I was followed by the first global pandemic – the Spanish Flu – driven by the enormous worldwide movement of people, which killed another 50 million, including at least 12 million Indians.

India had hoped for a ‘better deal’ if they joined in the war – this deal never came.

In 1922, a disillusioned Rabindranath Tagore wrote:

“The West comes to us, not with imagination and sympathy, that would create and unite, but with a shock of passion – passion for power and wealth – passion that is a mere force, which has in it the principle of separation, of conflict.”