Reading Time: 8 minutes

Rail travel in the sixties and seventies was a journey through time and space. To travel by train one had to plan much in advance. Bookings opened one month before and there were always long queues but it was easy if you knew someone in the railways who could get your ticket from the VIP quota. My travels as a child were mostly to a small town called Jhansi. We would travel by Punjab Mail from Mumbai to Jhansi. The train left Victoria Terminus (VT Station) at 2.30 in the afternoon and reached Jhansi the next day approximately by 1pm. There were only fixed departure times, arrivals were dependent on many factors and it was not uncommon for trains to be 5 to 10 hours late.

Every summer vacation I would make this trip. My earliest memory is of the steam engine if one looked out of the window little specs of coal would get into the eyes and nose face etc. Coal specs would be littered all over the compartment. You could book a coupé and on an extra payment the railways would provide a tub with ice that would cool the compartment. There was something majestic about the steam engine, the hiss and clang, the chugging, the whistle and the power of the engine that pulled the train on its long journey. These engines fuelled by coal were in awesome sight. There was a gradual transition to the diesel locomotives but the rhythmic puffing of the steam engine added a nostalgic charm to the journey.

Food was always an important and exciting aspect of travel. There would be a dining car that was attached to the train and from this kitchen, food would be served to the passengers. But the joy of travel would be the food that one ate from the vendors at various stations. At Kalyan one would get dinner on the station from the dining car, vendors on stations would be selling Puri Bhaji and Chivda. At Kasara and Igatpuri there would be Batata Vadas, two pieces in a small white paper bag and Puri Bhaji. At Manmad junction there would be Puri Bhaji and various other foods. In Maharashtra Batata Vada, Puri Bhaji and Poha were standard fare that was available at most stations. The trains would stop at Manmad for 25 minutes to refill the water tanks above. Similarly in the morning at Itarsi junction the train would stop for water refuelling and toilet cleaning.

There would be Tea in khullads, small earthen glasses made for tea. Every station had Chaiwalas through the day and night would walk the length of the train on either side shouting “Chai Garam Chai ”. For which there were always customers. In the forties to popularise Tea there were sign boards that said “Garmi me Garam Chai thandak puhchata hai” (In the summer hot tea cools you down), bread pakodas, sandwiches, Poha, Chana puri and a variety of other breakfast foods. Freshly made and served hot. Breakfast would be served at Bhopal junction. Between Itarsi and Bhopal the dining car boys would take orders and serve breakfast. There would be greasy omelettes with bread butter and a little plastic thermos of hot tea or coffee served in plastic glasses. Between Bina junction and Jhansi, lunch was served from the dining car. My mother and I would get down at Jhansi and our journey ended. But from Jhansi to Delhi was also a culinary experience. At Gwalior station one would get Jalebis eaten with Dahi or Rabadi. At Morena one would buy little bottles of scented elaichi seeds. At Agra there was Petha and Dalmoth and At Mathura one would buy Pedas and north of Delhi Chana Bhutara / Kulcha and in the winter Sarso ka Saag and Makai ki roti were on the menu. A vendor selling Chana-Dal and Aloo eaten with puri or lucchi made himself popular by calling “mai puri lucchi ”. Of course the pun was obivious to every woman who passed his stall. In North & Central India, there would always be the smell of oil frying, hot samosas and kachoris and puris. Almost every station had a food speciality.

In the 60s, the culinary experience on Indian Railways was different from today’s onboard catering services. The dining car provided standard Thalis includes Dal and Aloo ki Sabji and salad consisting of Tomatoes, Cucumber and onions. There was a little pickle that accompanied every Thali. If you ordered a special Thali there were cutlets that were made of beetroot, potatoes and vegetables, at an extra cost. Similarly there was a non-vegetarian Thali that consisted of two pieces of chicken in curry, rice, chapattis and vegetable salad etc. In Nagpur a Railway caterer invented a dish called the Railway Chicken. This caught the fancy of the upper-class and became a popular party dish, and even today there is something called Railway Chicken.

Passengers often carried their own food for the journey, and one always packed a little extra to share with fellow passengers. At railway stations, the food available was reflective of the local culinary traditions and varied across regions. Slowly but surely these vendors have shut shop and they have been replaced with modern fast food joints and this is a big regret for me.

Also what has disappeared from the Railway station are Toy vendors. There would be push cards selling handmade toys, the Kathakali doll that would shake with a little nudge. The little Taj Mahals in a glass case, monkeys beating drums, all kinds of whistles, little drums, dolls, musical and string instruments, miniature kitchen utensils, a whole range of Indian handmade toys that have now completely disappeared.

One of the enduring charms of train travel in those days was the scenic beauty that unfolded outside the windows. As the trains traversed through picturesque countryside and rural landscapes, you were treated to a visual feast of India’s diverse topography. The journey itself became a meditation, a slow passage through the heart of the nation. As the trains burrowed into the guts of cities and towns and rolled past the houses of the people living alongside the tracks. One could see an India far removed from the urban towns. Every time a train chugged in and out of the station, one would see little boys looking at the train in awe reminding one of Appu in Satyajit Ray’s “Pather Panchali”. Every boy hoping to get on to the train for a better future.

Overcrowded trains were a common sight, especially during peak travel seasons. A microcosm of Indian society spanned the train from one end to the other. Train journeys provided a unique platform for social interaction. Passengers engaged in conversations, sharing stories and experiences. The camaraderie among co-travelers turned strangers into temporary companions, creating bonds that lasted for the duration of the journey. Often exchanging addresses and promises to write letters.

Luggage consisted of one trunk, one holdall, one Surai (earthen water container), one bag, the holdall was a unique contraption a versatile and spacious bag in which one could fit in a mattress, blankets, pillows and a lot of other stuff for which there was no place in the trunk. It was a contraption unique to India and from here was exported to other parts of Asia. After all the material was put in it was rolled and firmly held by two leather straps. It was functional, durable, made of green canvas and lasted for a generation. Every girl who got married was given a trunk, holdall and Surai. Some of these Surai were fashionable made of copper with a cloth covering that was embroidered.

There were taps on every station and you ran out to fill your water bottle or Surai. They were large earthen pots (Matakas) placed on the Railway station and you could get free water in your own container. Giving water to people was a pious deed. Nobody thought of selling water.

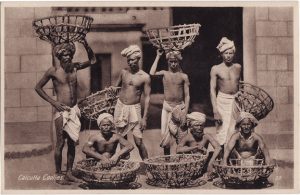

Unlike today’s trolley luggage, passengers in those days had to manage their own luggage. Porters were available at railway stations, ready to assist with the heavy bags and trunks, yet the negotiations were a process that one had to go through. Generally, the porter (Coolie) won. The absence of modern amenities like trolleys made the process more labour-intensive, yet it added a personal touch to the travel experience.

The challenges of train travel in the 60s, including manual ticket booking, overcrowded trains, and communication constraints, were offset by the unique joys of the journey. The unhurried pace, the scenic landscapes, and the social interactions contributed to an experience that was both challenging and fulfilling. Another aspect of travel in those days was taking food for friends and relatives who were passing through your town. I remember my grandmother would often take a full lunch to the station. Trains often stopped in Jhansi for thirty minutes which was enough to serve the meal and exchange all the news, gossip of the family. In case the timing was different, instead of lunch my grandma would take aloo ka parathas, a khullad of Dahi and some mithai (a Khullad is a clay pot). Going to see someone off the station was a ritual by itself. A little sobbing, hugging was a part of the rituals. Sometimes a family of eight to ten would go to see two people off. Similarly, going to the station to receive family was mandatory.

Vintage train tickets

In retrospect, traveling in India by train in the 60’s was an adventure by itself. It was a period marked by the coexistence of tradition and modernisation, where steam locomotives shared tracks with diesel engines, and where the class divisions in train compartments mirrored societal structures. The challenge of transporting yourself from the narrow gauge to the broad gauge meant getting off one train and crossing over to another could mean walking up the stairs, crossing the bridge and getting to the other stations was a task. A good TT (Travelling Ticket Examiner) would hold the train till old Maaji would get into her compartment. Reservations were printed on a chart that was stuck outside the door of the compartment with your name and seat number. The TT had its own chart that correlated with the names printed outside the compartment. For a little fee (Bakshis) he would allot you a seat, a berth. In those days a TT was an important person in the clog of the railways.

The challenges of that era have given way to a more streamlined and efficient system, but the memories of those journeys linger, etched in the collective consciousness of a generation that experienced the magic of train travel in a bygone era.