The series by Sanjay Leela Bhansali, may not have set the streaming world on fire, but Heeramandi did bring into focus the tawaif, who used to be a staple of mainstream Hindi cinema at one time. If not as a romantic, vampish or tragic character, she appeared as the ‘item girl’ of those days, as filmmakers found excuses to add mujra into their films for oomph or popular appeal. As Hindi cinema got more urbanised or westernised, she was replaced by the cabaret dancer and later by the bar dancer, and now by the heroine who is willing to gyrate in skimpy costumes.

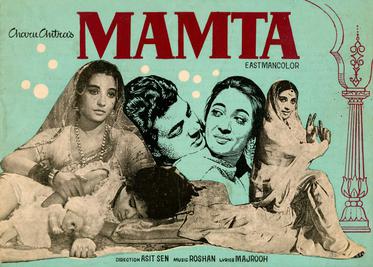

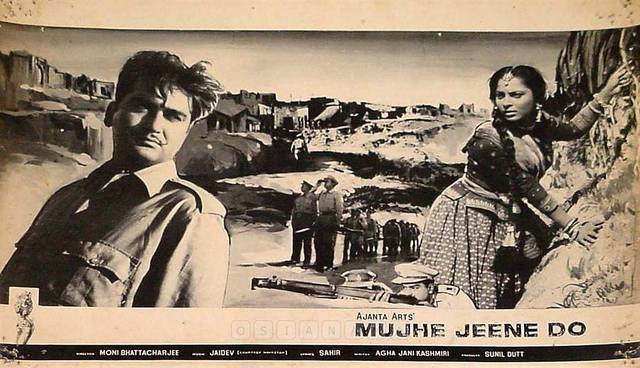

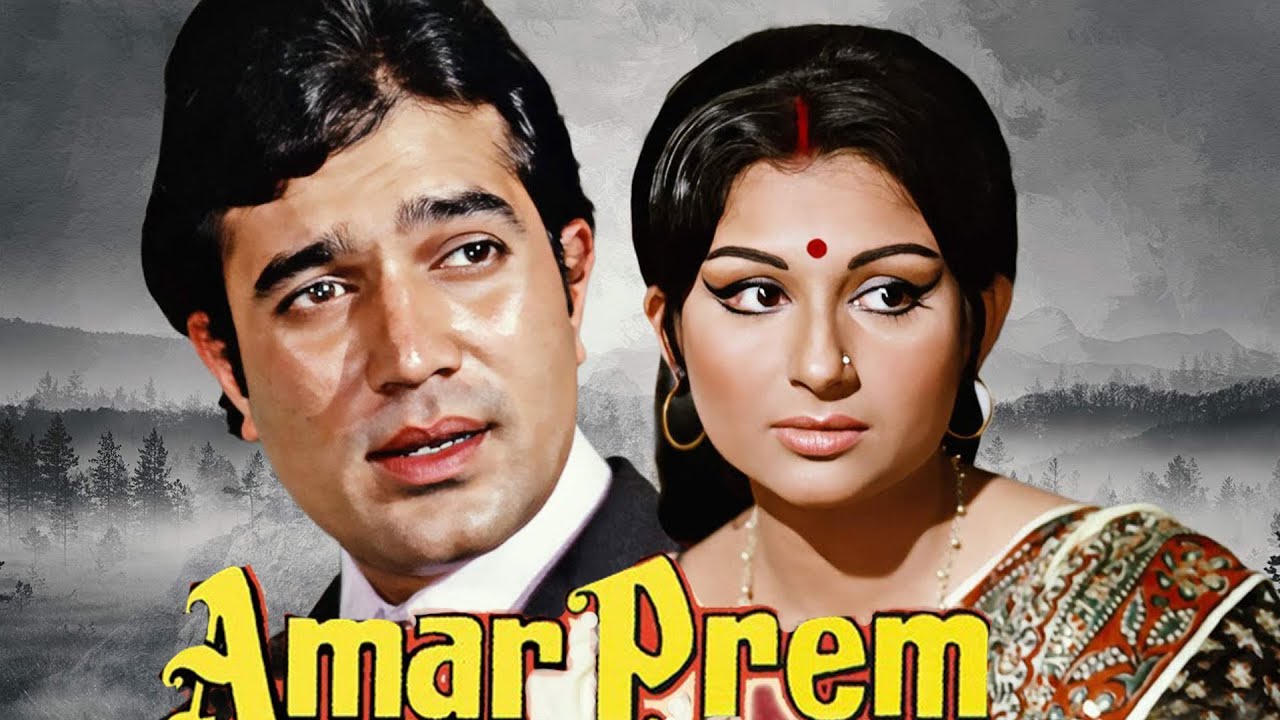

The term courtesan is used as a catchall to describe tawaifs, devdasis, nagarvadhus, or women who used either performing arts or sexual wiles to entertain and entice men. The tawaif culture, however, had its own ethos and style of dance and music. These women, usually forced into the profession by birth or circumstances, did depend on wealthy men who patronised them, but were not necessarily sex workers. The women of Shyam Benegal’s Mandi (1983) or Bhansali’s Gangubai Kathiawadi (2003) were not tawaifs, but prostitutes. Chitralekha (1964), Amrapali (1966) and Vasantsena of Utsav (1984), were courtesans, but not tawaifs. The leading ladies of Devdas (several), Vyjayanthimala in Sadhna (1958), Nargis in Adalat (1958) and Suchitra Sen in its remake Mamta (1966), Waheeda Rehman in Mujhe Jeene Do (1963), Sharmila Tagore in Amar Prem (1972) were in the profession and on the outskirts of respectable society, but were not common sex workers.

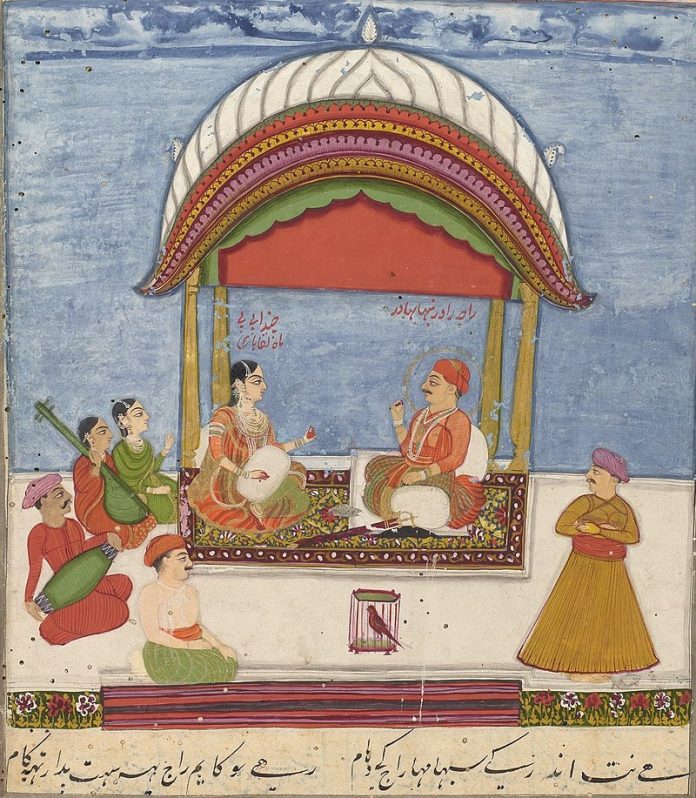

Tawaifs were educated at a time when most women were forbidden to learn, they were taught classical music and dance by ustaads, and also etiquette and refinement. Many of them were poets and writers, but as it always happened, the artistic achievements of women were either appropriated by men, or neglected altogether. Sons of nawabs were sent to them to learn tehseeb and also the appreciation of the finer aspects of high society and aristocratic culture. The women may have, in many cases, been forced into sex work, but at a time when women were confined to the home, the arts and religion were the only means to negotiate some measure of independence.

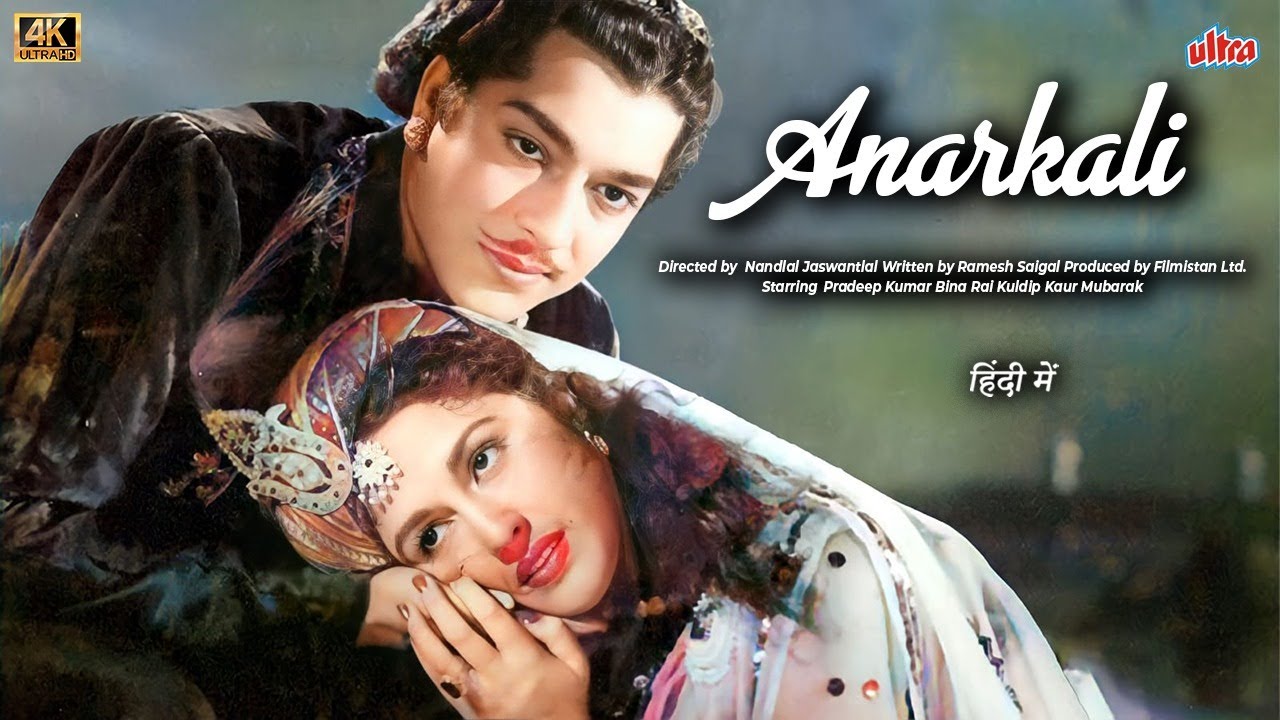

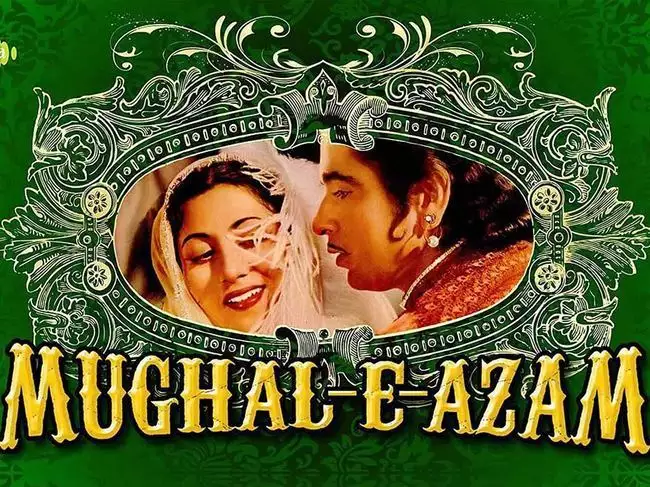

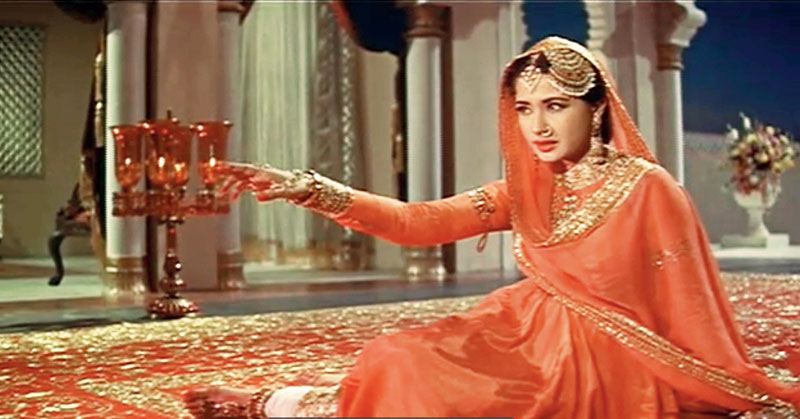

The most famous tawaif in popular cinema is Anarkali, who made two appearances in movies—played by Bina Rai in the eponymous 1953 Nandlal Jawantlal film, and by Madhubala in K.Asif’s timeless epic Mughal-e-Asam in 1960. The famed beauty, named Anarkali by Emperor Akbar, caused a crisis in the Mughal Empire; Prince Salim led an armed rebellion against his father when he was commanded to give up the courtesan and marry a princess befitting his royal status.

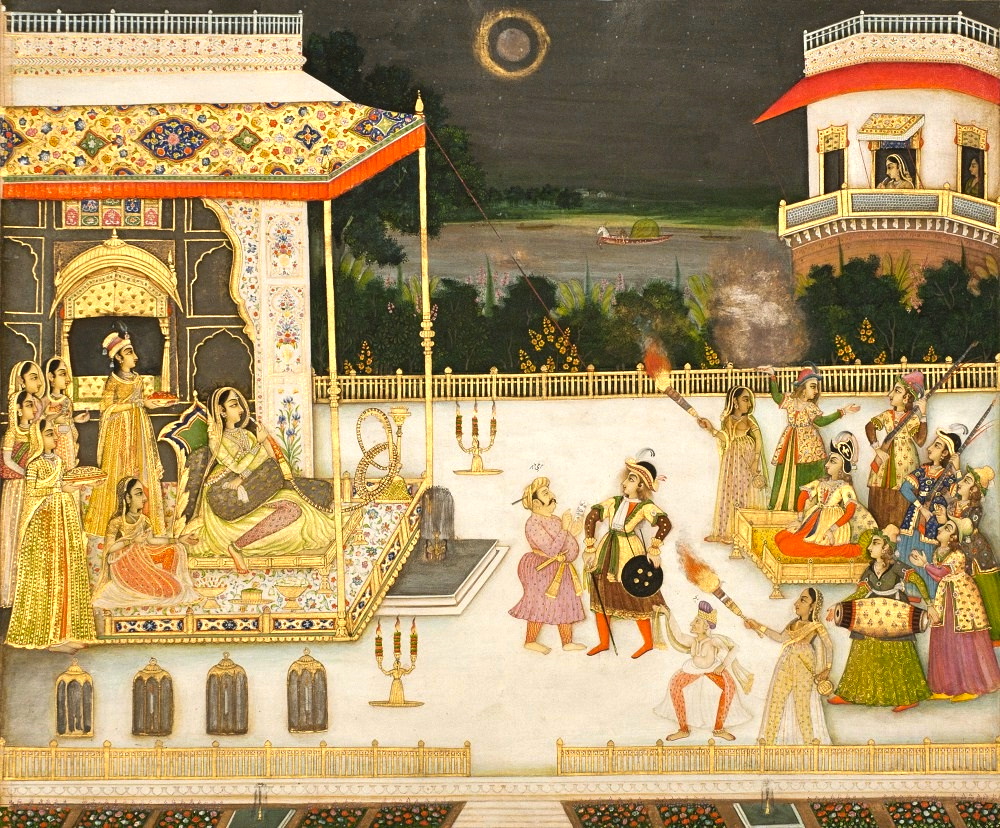

In the Mughal era, the most accomplished tawaifs performed at the court, and by association with the aristocracy acquired a certain measure of power and influence. When the seat of the Mughal Empire was in Lahore, they settled into the areas around the palace and the grain market Heera Singh Ki Mandi became Heera Mandi, the centre of the tawaif culture in the city, with its own financial ecosystem of musicians, vendors and procurers. The opulence and grandeur that Bhansali had depicted in Heeramandi, is exaggerated, but some of the women did live well if their patrons were generous, even if they did not get the respectability or social acceptance accorded to the wife.

Image courtesy: koimoi

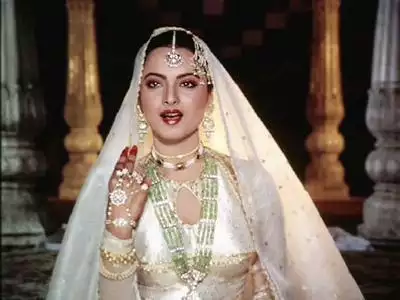

Two other period films that portrayed the glory of the Lucknow tawaif were Kamal Amrohi’s Pakeesah (1972) a Musaffar Ali’s Umrao Jaan (1981)– also remade as a forgettable copy by JP Dutta in 2006— the former in which a tawaif (played by Meena Kumari) seeks entry into the upper echelons of aristocracy when a nawab falls in love with her, and Umrao Jaan (played by Rekha and in the later version by Aishwarya Rai), was based on Mirsa Hadi Ruswa’s novel about a courtesan-poet, who may have been inspired by a real character. Her story was probably the most authentic—as a child she was sold to a kotha and trained in the arts. Later, when she falls in love with a nawab, she is not considered a suitable match for him. Rejected by her family, abandoned by the men she depended on, she pours her heartbreak into her poetry, and is left bereft after the Mutiny of 1857, returning to a looted and deserted kotha. The scene symbolised the turning of a page in history.

The classical golden period of the tawaif faded out during the British era—and yes, many did participate in and support the freedom movement, like Heera (played by Rani Mukerji) of Mangal Pandey (2005) and the young women of Bhansali’s serial. Heeramandi lost its lustre, and the accomplished singers and dancers were replaced by gauche women swinging their hips to movie tunes. Many early theatre and film actresses were from Heeramandi or Lucknow or other tawaif gharanas. There were also film producers, studio owners, recording and radio artistes– some of them making a smooth landing into modern times, while the ones who could not or did not adapt were lost to time. Ruth Vanita in her book, Dancing with the Nation: Courtesans in Bombay Cinema (2017), wrote, “Jaddan Bai, mother of Nargis and grandmother of Sanjay Dutt, was a daughter of courtesan Daleepbai of Allahabad. Jaddan was a pioneer in Bombay cinema, working as an actor, singer, music composer, director, and producer of films. Fatima Begum, actress in silent films and the first woman director was from a tawaif family, and had a long-term relationship with a Nawab. Bibbo, actor, singer, and music director in the 1930s and 1940s, was the daughter of courtesan Hafeesan Bai of Delhi.” Gauharbai was a powerful producer in her time, setting up and running the legendary Ranjit Studio with Chandulal Shah.

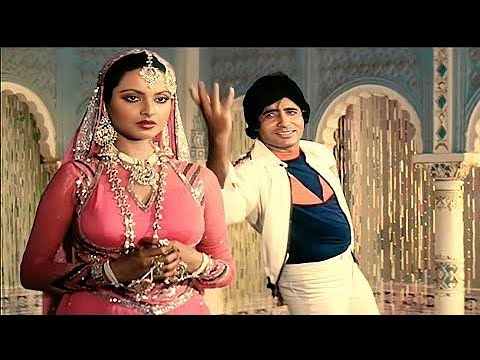

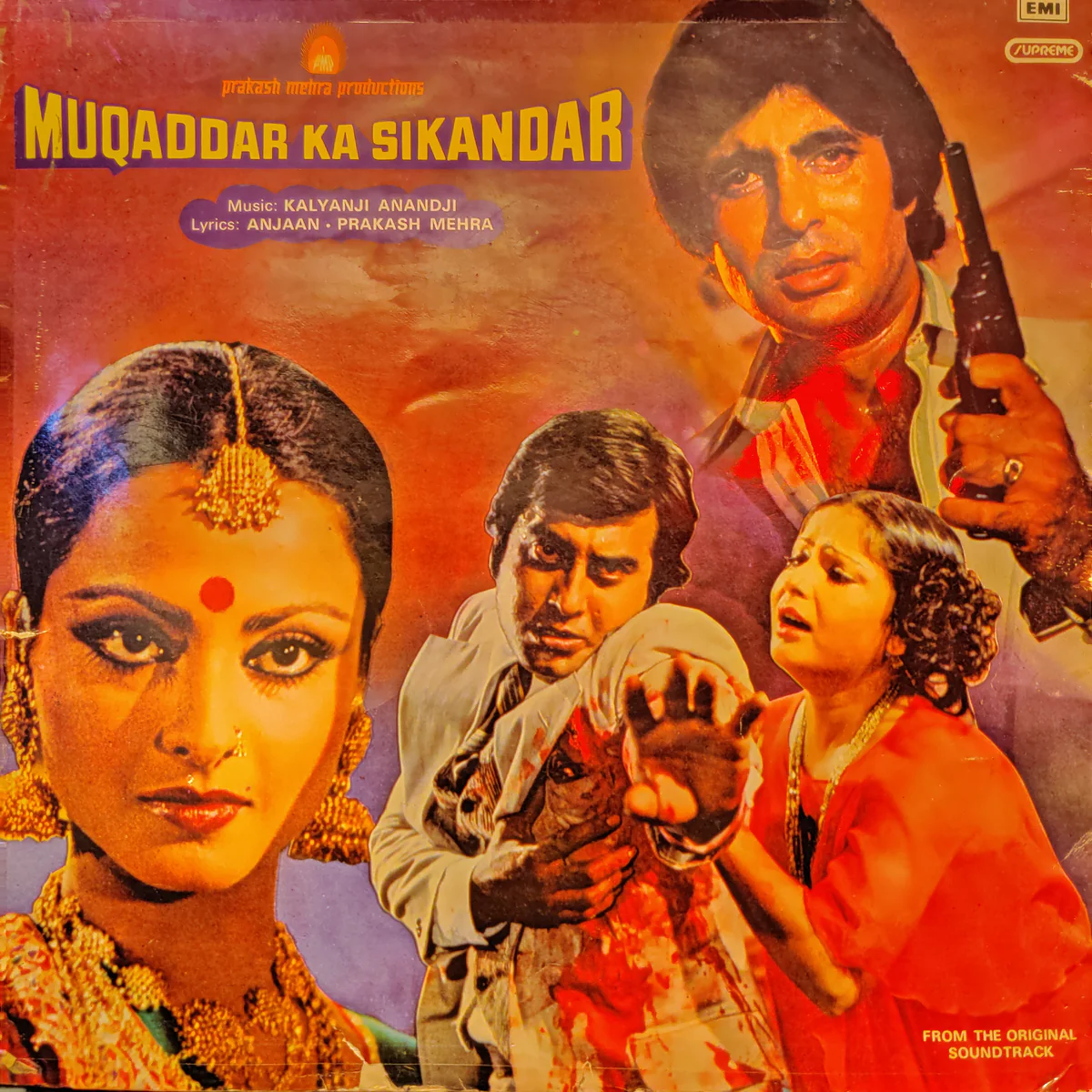

Rekha in Muqaddar Ka Sikander

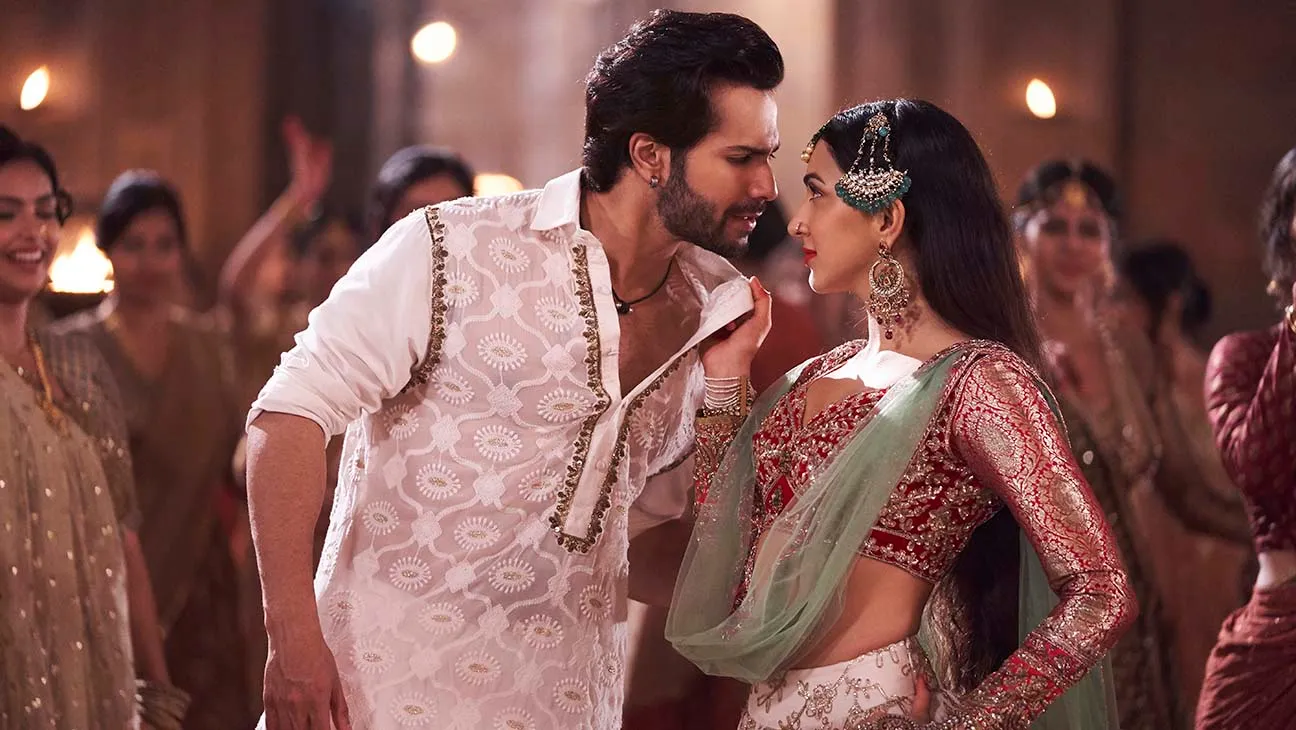

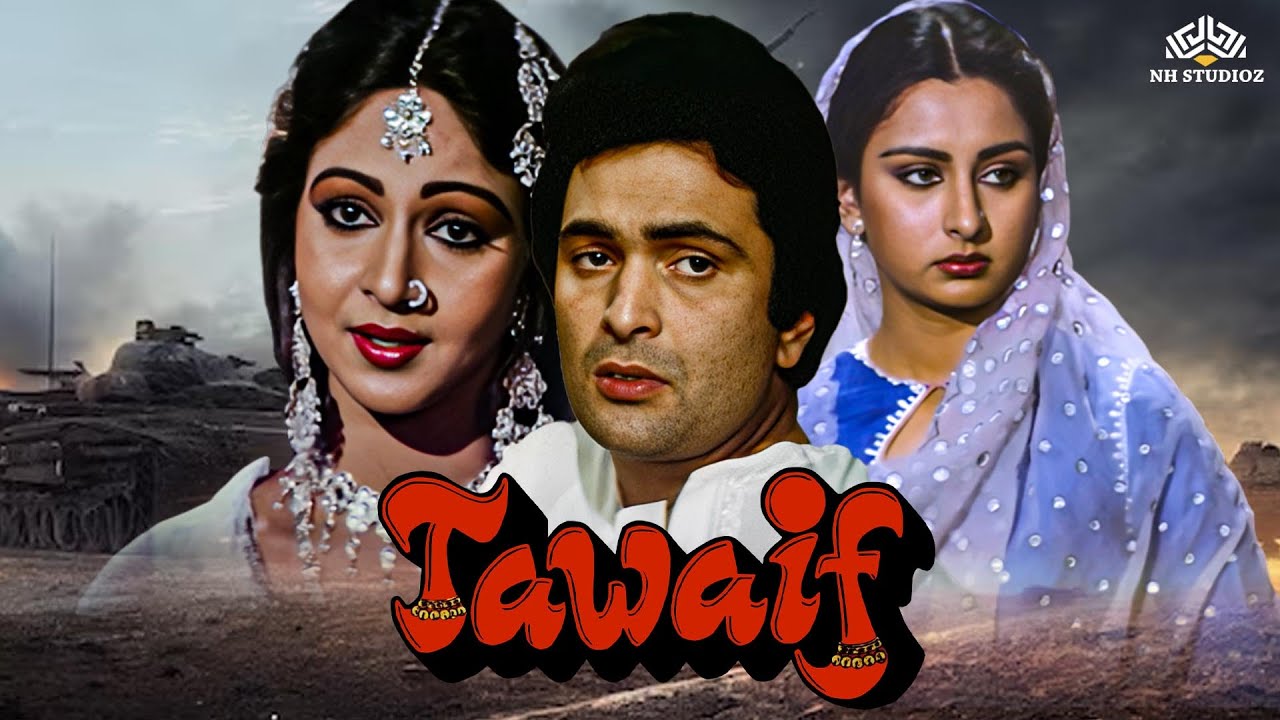

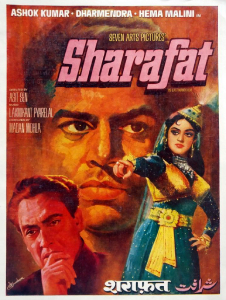

By the time, the tawaif came to be seen as the item girl of mainstream cinema, she fell into the stereotype of the vamp who had a change of heart in the end and sacrificed herself for the hero, the good as gold victim who needed rescuing by the leading man. Most, the leading actresses of the time – Hema Malini in Sharafat (1970), Mumtaz in Khilona (1970), Rekha in Muqaddar Ka Sikander (1978), Rati Agnihotri in Tawaif (1985), Tabu in Jeet (1996), and most recently Madhuri Dixit in Dedh Ishqiya (2014) and Kalank (2019), played some form of the tawaif, even after the character had become outdated. The tawaif was still an attractive part for an actress to play, because of the dancing, enhanced emotions, the feminine airs and graces and of course, the ultra-glam costumes.

The Heeramandi of Bhansali’s imagination, is now derelict. The feudal lifestyle of leisure and pleasure-seeking in kothas is over. Which is why it has been years since a traditional mujra was seen in Hindi cinema and the series was able to evoke such strong nostalgia among Indian viewers and outrage among Pakistani, who see their language, culture and heritage stomped over by a Bollywood moghul. But then Hindi cinema has always been stronger on drama than history.

Anarkali

Mughal-e-Azam

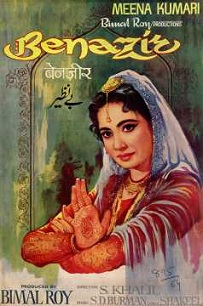

Benazir

Mamta

Pakeezah

Image courtesy: Telegraph India

Muqaddar Ka Sikander

Devdas

Sadhna

Kalank

Umrao Jaan

Mujhe Jeene Do

Ghungroo

Tawaif

Sharafat

Khilona

Mangal Pandey

Amar Prem

Mirza Ghalib