Prem, a nonagenarian, recalls the trauma, turmoil and uncertainty of migration from the North West Frontier Province to India at the time of the Partition of the country, and then again from the beautiful valley of Kashmir to Jammu due to the militancy and changing circumstances. In conversation with Malti Gaekwad.

Born in 1931 into a family of freedom fighters from Punjab, Prem had a comfortable and much protected childhood. Her father Shri Jagat Ram Sethi belonged to a very well to do business family, he was well educated and an expert in his field of paper and pulp engineering. Their family funded and supported the freedom struggle and Prem’s grandfather and paternal uncle were imprisoned many a time along with Lala Lajpat Rai and Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan and other such leaders.

As a child she remembers: “Many freedom fighters and leaders used to regularly visit my grandfather’s home. One incident was when MK Gandhi had visited our mohalla and was telling the ladies to use the charkha and weave cotton……. my grandmother whom we called Beji or Bebe went to Gandhi and urged him to come to our house. She took him to an interior room where her charkha was kept, the room was full of many cotton bales. It seems she told Gandhi that she had been spinning yarn since the time he wasn’t even born!”

Although the family had businesses and lived largely in Lahore and Rawalpindi, Prem’s father travelled to various places across the country due to his assignments of setting up mills. In fact, Prem was born in Calcutta while her father worked there on his return from studies in the US. At that time, he was one of the few Indians who went to a foreign university for higher and specialised studies.

Having schooled in various cities including Jagadhri, Saharanpur, Lucknow, Nagpur, she finally finished school from Sir Ganga Ram School in Lahore.

At the time of her matriculation she was in the hostel, this was March 1947. From March 4 onwards there were reports of communal riots in various parts of the Lahore city and curfew had been imposed in the more sensitive areas. “There was lot of confusion and uncertainty all around and we were sure our exams will not be held on schedule. Despite the tension there was a child like joy within at the thought of the cancellation of the exams. But much to our surprise…. on the evening of March 7 the radio announced that starting tomorrow morning exams will be held on schedule each student should try to appear for as many papers as possible,” she recalls.

“Our school itself was our exam centre and since we lived in the hostel, we managed to appear for all the papers. Soon after the exams were over, I was safely back home in Karachi with my family. Much uncertainty prevailed about the results, while the rioting had increased and people had started migrating to safer places with their families. No one had any idea about what was going on… not in the least about the division of the country.”

The riots were instigated and fuelled by the British as we all know, by showing Jinnah the dream of having his own country, whereas initially the idea was to oust the British from our country.

By this time Prem’s father Jagat Ram Sethi, having successfully cleared the UPSC exam of undivided India was selected and appointed the Director of Industries, Sindh Government at Karachi. (It was well known that the local administration could not find a suitable Muslim candidate for the post, for which they were keen.) Prem’s family secured provisional admission for her in the JD Sindh College. There seemed a remote chance of getting any results at that point of time. So during the short period she had the privilege of going to and back from college in her father’s official car as it was not conducive environment for girls to go out alone!

Soon it was the summer of 1947. Prem recalls that there was a bulky and flourishing Pathan who lived in the vicinity of their home. His huge estate so to say was called Illaco house. He was known to give shelter to Hindu families, especially women and children under his strong protection and help them get a safe passage to India by air or surface transport.

Meanwhile, one day Prem’s younger brother Romesh, on his way home from school heard that the Matriculation result had been declared. Prem had passed and eventually managed to get her certificate from the authorities. However, the political and social situation was getting worse day by day. It was difficult for children to go to school and college and the family felt that Prem and Romesh should be sent away to a safer place near Delhi.

Fleeing to safety

Unfortunately Prem has no specific memory of August 15, 1947, the Independence of India or the excitement of India’s freedom. By that time her grandfather Lala Moolchand and her eldest uncle Lala Kashiram Sethi, the real freedom fighters of the family, were no more, and most of the large joint family had been disintegrated and separated. Some moved to what they thought were safer places or for some employment. However the fact remained that theirs was a well-known Hindu family still in Karachi, and they were quite isolated and apprehensive about the events unfolding.

Reports came regularly of Hindus being killed and looted indiscriminately, young, old, women and children. Thus the decision to send them to Mumbai was taken. In early September, Prem, her mother Dayawati and younger brother Romesh boarded a ship called SS Ekma and set sail from Karachi for Mumbai, (then Bombay) while the youngest sibling Inder Mohan remained with the father. Trains were not safe and in any case overloaded with people trying to escape. The ship usually would take them to Bombay in a day and a half. As children, Romesh and Prem were excited about travelling by ship, roaming on the decks, and visiting various parts of the ship as they had heard many stories from their father’s trip abroad. This was a steamer which regularly sailed between Bombay and Africa… now it had been deployed to transport Hindus to India.

All their excitement soon turned to disappointment. The ship was overloaded with migrating families. Although Prem and family had a small cabin to themselves, the two kids wanted to explore and saw pathetic scenes on the decks. Their walk around the ship was rather dismal, fraught with danger as the sea was very rough and the ship was rocking furiously. People were sick and vomiting all over the place. Besides being overcrowded the ship became dirty, stinking, and very messy. Soon the youngsters receded to the quiet comfort of their cabin. The journey and ordeal lasted for three full days due to the rough seas. They were relieved on finally arriving in Bombay and being received by their cousin, Suraj Balram Sethi (son of Lala Kanshiram).

Then within a few days they took a train journey to Gwalior and Prem was admitted in the Kamla Raja Girls College and Romesh in the Scindia School on the Fort – both with boarding facilities. Getting admission was difficult in midterm but were admitted reluctantly. There were no science subjects in the girl’s college and Prem had to be content in taking music as her subject – much against her wishes. After settling these two children in Gwalior, Dayawati wanted to go back to Karachi to join her husband but could not as by then the Kashmir operation had started and all the flights (at that time India had only seven planes) were diverted to carry troops and supplies to Kashmir.

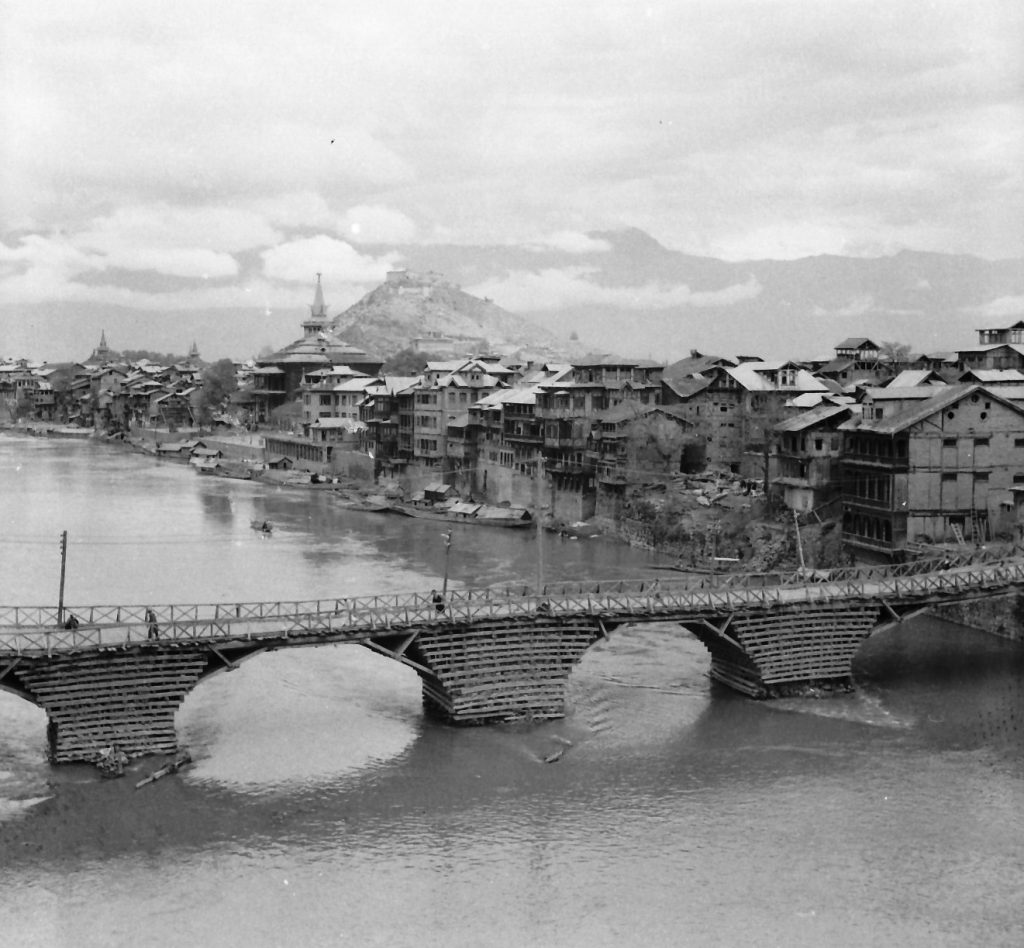

Later on in life she recalls the situation during the Kashmir Operation in October 1947… India was supposedly independent of the British by that time but in the state of Jammu & Kashmir there were still disturbances as the Maharaja had not formally joined the Indian dominion. Soon Pakistan sponsored insurgency in the Kashmir Valley became virulent. Prem recalls hearing stories from her father-in-law Diwan Chaman Lal Sahni (who had himself migrated from Rawalpindi and settled in Srinagar) about the difficulties and tension the Sahni family went through at that time.

Fear psychosis

The situation in Kashmir valley in the last week of October ’47 was uncertain and full of fears and scare. Reports reached Srinagar of Pakistani invasion, the people in Srinagar were fearful of the future. On the night of October 25 the semblance of governance seemed to have evaporated, there was no administration in action. The Standstill agreement was promulgated but Pakistanis deliberately started choking Kashmir of essential supplies.

The law and order in the city was in a mess. Everyone had their eyes towards the skies waiting for Indian planes carrying troops for the defence of Srinagar. Lack of communication fuelled their fears. No newspapers had come in from Lahore for over a week and not many people had radios; transistors had not arrived till then and so the air was thick with rumours. There were not many telephones either and no trunk calls could be made, thus no one knew what was exactly going on. Nights were spent taking turns with guns, sitting in the loft of the house. All night voices of the locals going around streets saying “Humlaawar Khabardar hum Kashmiri hain taiyaar” (invaders beware – we Kashmiris are prepared.) Of course there was no need to use a gun but nonetheless such was the fear psychosis.

On October 27 airlifted Indian troops started landing and people were somewhat relieved. But on the same day so called Kabalis (tribals) led by Pakistani Army officers invaded, entering Baramullah ruthlessly indulged in loot, killings and destruction.

Seeing the uncertain conditions, it was decided by the family, that the ladies namely my mother and sister-in_ law, should be sent out of Kashmir for the time being. The planes which were bringing in the troops were going back without much load except some refugees who could manage to reach the airport and flown to Delhi. My husband, Sati, arranged with a pilot to help out. His only stipulation was that they should be at the airport at 0630 in the morning and get them registered. However, there was a major problem as there was not much cash available at home since all banks had been closed for the last 10 days. We did not have any close relatives living in Delhi, so were not sure where the two unescorted ladies could go on arrival in the big city. It was then decided that they would get some Taby silk sarees from a family friend on credit to fill a suitcase, along with some personal jewellery to sell in Delhi to get cash if need be.

The next problem was getting to the airport at that early hour. A tonga was arranged to take the ladies to the airport. The tonga with the two ladies, my husband and his father left home at 4am because the last two miles to the airstrip was a steep climb. The tonga wallah and the two gents had to push the tonga up the steep incline which took about two hours, and after arrival registered them to be put onto the next flight. They had only the address of an acquaintance in Delhi, but had no idea if the ladies would be able to find and reach their residence. One can imagine the desperation they were in as literally they were left in the hands of God. On the thought that they may never meet again!! It was after about almost two weeks that a message came with some people coming to Srinagar, of their welfare and safe arrival. It was many months before they all met again.

In 1956 Prem was married to Satpal Sahni and a new chapter in her life began in Srinagar (Kashmir). Her husband was a correspondent for The Times of India. The beautiful valley of Kashmir was always buzzing with activity especially in the summer, and here Prem got to meet many people from different walks of life, politicians, business leaders, actors and more; besides visiting different scenic parts of Kashmir with her husband and family. This was probably the golden period of her life. While pursuing a busy social life, Prem briefly also wrote for the women’s magazine Femina. In the meanwhile three children were born to the couple.

The wars of 1962 and 1965 gave Sati an opportunity to specialise as a war correspondent

and he covered all the four wars of Independent India from the front as a multimedia journalist, along the way collecting some priceless photographs and documents. Apart from looking after the children, Prem involved herself with her mother-in-law Sarla Sahni in social welfare activities for the jawans and their families. Adventure and mountains fascinated Prem. In more peaceful time she undertook a course in adventure sports and eventually did a mountaineering course with none less than Tenzing Norgay, the famous Everest climber.

Trouble brews again

But all good things come to an end sooner than one expects. In the ’80s trouble was brewing again in Kashmir. Demonstrations and riots, strikes and stone pelting mobs slogan shouting groups became an everyday affair. Towards the late eighties things were getting really bad more strikes and uncertainty, schools and colleges were shut off and on, due to the hartals called by one group or the other shops and bazaars remained closed indefinitely, and regular confrontations between the demonstrators and the police leading to stone pelting, lathi charge and sometimes the use of tear gas to disperse the crowds became common. Mostly the processions passed through the downtown areas of the old city of Srinagar but a lot of these activities happened in the famous Lal Chowk which was not even a kilometre away from the Sahni household.

“We were very much in the heart of it, my husband was a journalist and got all the news from all over. Our house being on the main road we could see the armed police and their vehicles from our house. The police had also pitched tents in the garden Pratap Park right opposite our home. One day we heard that during a scuffle with the police one unruly demonstrator snatched away the gun from the police personnel and opened fire at the police! It was after this incident that all security men carrying guns were given chains like the ones used for dogs, to clamp their guns on to their belts.”

Prem recalls “…At the end of 1989 I went to Delhi briefly for a wedding with just the suitcase full of few clothes but did not realise that I will not be able to return. My husband too had been getting life-threatening calls, and posters in Urdu were being stuck outside our house telling us go away. Meanwhile my husband had to attend a meeting in Jammu and while he was there he got a handwritten note delivered anonymously by someone on a printed letterhead of a militant outfit telling him “Don’t dare to return to Kashmir if you want your safety, stay where you are…” meaning Jammu.

That hit the nail on the head; we decided not to go back for the time being especially since it was winter too. My father-in-law was old and was already in Jammu for the winter months. We hoped to go back to Kashmir in the summer like every year. Our elder son and was working in Srinagar on a business project with a close friend and continued to be there.

On January 28, 1990 the most unimaginable and horrific thing happened. My son and his friend reached the factory together in one car and before they could realise what happened… his friend was shot point blank by two people with covered faces, in his own office. In a state of shock himself, my son rushed his friend to hospital but he could not be saved. That same evening my son flew out to Delhi with his friend’s body as the rest of the family was there, also never to return to Kashmir.”

By now it was clear to most Hindus that they were not wanted in Kashmir.

Many Kashmiri Pandits (Hindus) had been killed mercilessly and many fled to refugee camps in Jammu and some with better means or contacts went elsewhere. The heaven that Kashmir was, had now become hell, infested with various militant outfits each with a different agenda … even Muslims were not spared if they did not co-operate. In short, life in Kashmir was ruined.

Mission to Srinagar

“Meanwhile we attempted to settle in a rented house in Jammu yearning for everyday household things we had left behind in our residence in Srinagar where the family had lived for the past 50 years. We borrowed and bought a few essentials and I managed a house with the bare necessities. My father-in-law could not bear the thought of not being able to ever return safely to his beloved Kashmir, and his health kept deteriorating. My husband lamented the loss of his lifetime of hard work in the form of his very rare, treasured and valuable photographs, slides, camera equipment, books and manuscripts that were languishing in a locked house in Srinagar. We had left behind our pet dog too in the care of a Muslim servant who had been with us for the last 25 years. Ahmed Khan whom the children lovingly called Ammaji was as devoted as ever and continued to live in the outhouse and look after our home and dog but he was being threatened too.

I could not take all this any longer and decided to go on a do-or-die mission to Srinagar to retrieve my husband’s treasure and other belongings. No one,

I repeat no one, not even our children knew about my trip except my husband, who had surprisingly agreed to let me go. Only Ammaji and one more trusted Muslim acquaintance knew of my visit.

I undertook the 270 km journey by bus to Srinagar trying to be as inconspicuous as possible, very scared inwardly but with the determination to accomplish my task, no matter what. I carried only a small handbag with some food, a change of clothes, and a little bit of money. During the day long journey I didn’t dare to speak to anyone lest I give myself away.

Late evening I reached my home. Ammaji was there to receive me, it was such a relief to see him and our dog after such a long time. It was already dark outside and I was not allowed to put on any lights… did not want any neighbours or others to get alerted. It was time to rest after the long journey and before a hectic day ahead.

Up at daybreak, I got busy with the precise list of things my husband had given that I needed to pack and take along. Priority-wise we got started. Ammaji had already done some pre-preparations, collecting cartons, ropes etc which we needed a-plenty. After spending two days from dawn to dusk I had pretty much packed all that I could carry. On the morning of the fourth day while it was still dark, a pre-arranged truck arrived with some 2-3 labourers, and the furniture, trunks, a few cupboards and plenty of cardboard cartons were loaded onto the truck rather noiselessly, and we left for Jammu even before the sun showed up from behind the mountains. Ahmed Khan, Priya the pet dog and I, all seated next to the driver in the truck.

How much can one truck carry? Surely not everything a huge four-bedroom bungalow we had lived in for over 50 years contained. Still, I had the satisfaction of having successfully retrieved my husband’s treasured collection of photographs. Happy and elated at having accomplished this humongous task and back safely, I realised only much later that I had forgotten to bring my own clothes!”