Some analysts believe that post Covid-19 is an opportunity for India and China to resolve the ‘boundary question’, and seek a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable solution, writes Brig GB Reddy AVSM (Retd)

Can China escalate the ongoing border skirmishes – fist fights – in Ladakh and Sikkim into full-scale War? As per media reports, Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is moving troops to the areas of border skirmishes as a show of strength. In hindsight, they may not even raise the threshold to cross-border fire exchanges.

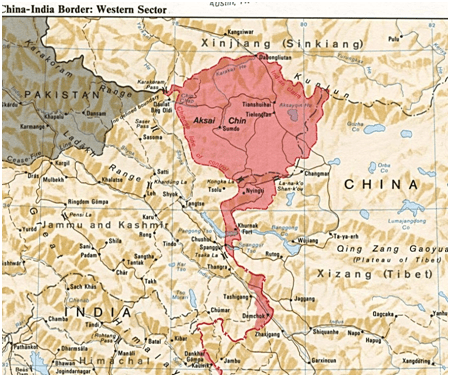

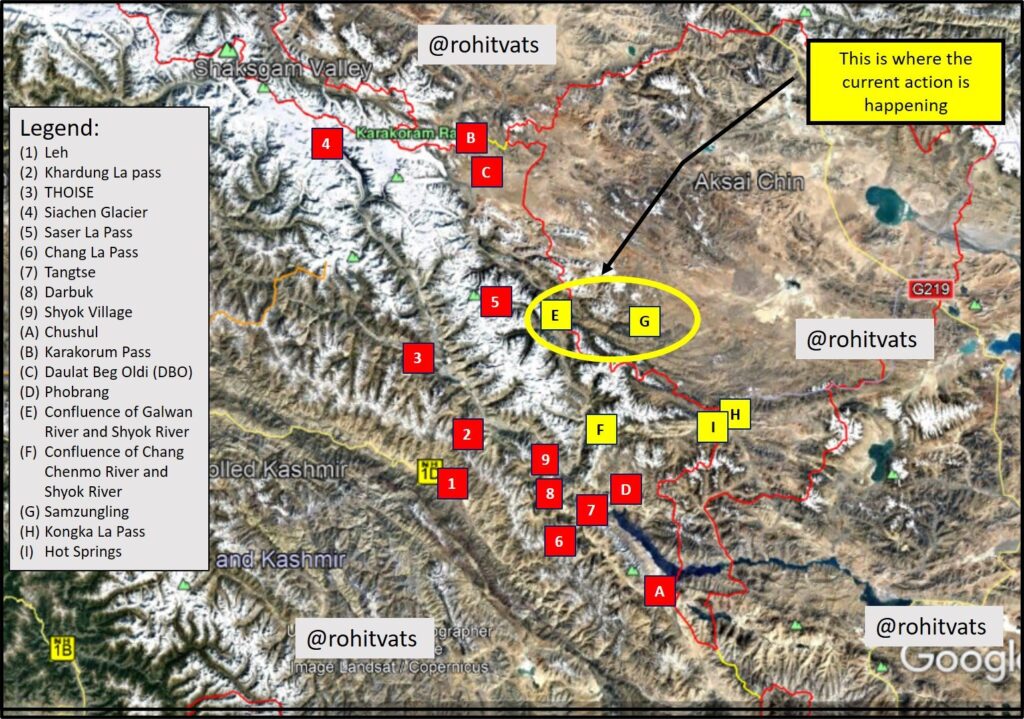

Why? They simply cannot afford to get embroiled in such a misadventure just as India cannot do it. At best, one can describe the ongoing fracas on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) along with Pangong Tso (one-third of the lake under Indian control) in Ladakh in the Western Sector and at Nakula in the North Sikkim in the eastern sector as cat-and-mouse game or shadow-boxing.

On scripted lines, each side is blaming the other side for the present escalating tensions on the LAC. The Chinese analysts are blaming India for aggression for “seeking to divert its domestic attention and pressure since the Covid-19 pandemic plunged its economy into recession”.

Since the outbreak of Covid-19, there have been some subtle and complex changes in China-India relations, which have created uncertainties for the improvement of bilateral relations, Qian Feng, director of the research department of the National Strategy Institute at Tsinghua University in Beijing, told the Global Times.Furthermore, “some scholars in India believe that the international environment for India is far more favourable than that of China. Under such circumstances, they believe the intensified confrontation between China and the US will be of greater help and benefit to India and advocate reaching out to the US,” Qian said.

On the military situation, as per Chinese media reports, Indian troops illegally crossed the boundary line in the Galwan Valley region along the border and entered Chinese territory. “More importantly, Song Zhongping, a military expert and TV commentator, told the Global Times that “India intends to make the border frictions with China a new normal, because it has geographical advantages to send troops to the border regions frequently. Although China won’t provoke India, the Indian military won’t stop their small operations from interrupting the Chinese military. This will be a prolonged issue between the two countries.”

As per PLA military sources, the Indian side built defense fortifications and obstacles to disrupt Chinese border defense troops’ normal patrol activities, purposefully instigated conflicts and attempted to unilaterally change the current border control situation. As per assessment of Chinese analysts, since China has a military advantage in the Galwan Valley region, the Indian military won’t escalate the incident. If India escalates the friction, the Indian military could pay a heavy price – a veiled threat. In a re-conciliatory move, the Chinese military source has stated the “the border troops of China and India will keep in touch with each other on the current situation through meetings.”

Also, the Chinese military sources stated that the actions by the Indian side have seriously violated China and India’s agreements on border issues, violated China’s territorial sovereignty and harmed military relations between the two countries. According to sources, the border troops of China and India will keep in touch with each other on the current situation through meetings and representations.

Three years ago in 2017, China and India were engaged in a 72-day military standoff in Doklam during Xi Jinping’s visit to India. Since then, measures have been taken to avoid another similar major incident. Nonetheless, nearly three-quarters of the transgressions, as per data since 2015, have taken place in the western sector of the LAC, which falls in Ladakh. The eastern sector, which falls in Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, witnessed almost one-fifth of the Chinese transgressions.

Let me highlight that border tensions have been endemic even after agreements reached in 2015 and Doklam in 2017. India and China have different perceptions about the exact location of the LAC in the Pangong Tso area, which results in high number of transgressions. While Pangong Tso tops the list, the other site of contention in the Galwan river valley had hardly witnessed Chinese transgressions, which was the scene of battle in the 1962 war. It is a “settled portion” of the LAC, where both sides agree on its location.

Maps have also been exchanged between the two countries and armies regarding the LAC in the Galwan River. However, construction of a new road in the Galwan area, well inside Indian Territory, has elicited strong objections from the Chinese who have moved soldiers, heavy vehicles, and monitoring equipment in large numbers. Sources said 70-80 Chinese tents have been pitched in the area, matched by strong Indian mobilization on the ground. Whilst one incident each was reported in 2016 and 2018 and four in 2017, there was no incident in 2019. So, the current situation in the area is a significant departure from the norms of previous disputes on the LAC.

As per official data, 80 percent of Chinese clashes in the disputed areas since 2015 have taken place in four locations, three of them in eastern Ladakh in the western sector. Trig Heights and Burtse have witnessed two-thirds of the total incidents. At Pangong Tso, Chinese transgressions almost doubled from a five-year low of 72 in 2018 to 142 in 2019. These transgressions occurred both in the waters of the lake, and its northern banks.

The first four months of this year, according to official data, witnessed 170 Chinese transgressions across the LAC, including 130 in Ladakh. Trig Heights recorded 22 per cent while Burtse/Depsang Bulge accounted for 19 per cent of all transgressions. The latest Chinese forays into Indian territory is in the Doletango area opposite Dumchele with 54 Chinese transgressions in 2019, after having recorded only three transgressions in the past four years.

Eastern Sector

The latest flare-up in the eastern sector is at Naku La in North Sikkim. In 2018 and 2019, there were two clashes reported each in 2018 and 2019 respectively. In Sikkim, there were 164 and 77 incidents reported respectively in 2015 and 2016. During the volatile 73-day confrontation at Doklam on the Sikkim-Bhutan border in 2017, there were 112 incidents. In the eastern sector, the highest number of transgressions by the Chinese — 14.5 per cent of the total – was recorded in Dichu Area/Madan Ridge Area.

Central Sector

The only location in the central sector to record significant Chinese transgressions is Barahoti in Uttarakhand which recorded 30 in 2018 and 21 in 2019. Least disputed, it is the only sector where both countries have shared maps, presenting their respective perceptions of the LAC.

In sum, the clashes on the LAC is a common feature that are escalated by the PLA on “His Masters Voice” from Beijing as part of their long-term strategy against India – their rival in South Asia. Viewed in the above context, if one wants to develop pragmatic assessments, one must follow carefully China’s past and present policies and strategies. No use in political and military jingoistic rhetoric.

During XI-Modi first informal Summit at Wuhan in April 2018, the two leaders “issued strategic guidance to their respective militaries to strengthen communication in order to build trust and mutual understanding and enhance predictability and effectiveness in the management of border affairs”. They also “directed their militaries to earnestly implement various confidence building measures agreed upon between the two sides, including the principle of mutual and equal security, and strengthen existing institutional arrangements and information sharing mechanisms to prevent incidents in border regions”.

However, on taking over reins, Xi Jinping endorsed former President, Hu Jintao’s; view that, “the first two decades of the 21st century as a period of “strategic opportunity” for its growth and development.” Xi Jinping has reiterated “respect each other’s choice of development path and each other’s core interests” to take advantage and prolong the window of opportunity. Unless compelled to do so, Xi Jinping may continue to pursue peaceful development path.

Xi Jinping is explicit with his “Two Centenaries” prescription for China to traverse: by 2021, when the CCP celebrates its centenary, complete the building of a modern socialist country that is prosperous, strong, democratic, culturally advanced and harmonious in all respects, with a strong military to make China the world’s dominant power by 2049, when Peoples Republic of China (PRC) marks its centenary.

As per Western strategic thinkers, Xi Jinping’s China is displaying a superpower’s ambition. They believe precise intentions of opaque, authoritarian regimes are difficult to discern, which is true. China formerly disguised its ambitions; but now is asserting them openly. China has entered a “new era,” Xi announced in 2017, and must “take centerstage in the world.” Two years later, Xi used the idea of a “new Long March” to describe China’s worsening relationship with Washington. Its relations are drifting away from “competitor and collaborator” towards “rival” status. What is most disturbing for China is its ongoing “Trade War” with the USA.

China has dramatically transformed in all fields under Xi Jinping – social, political, economic, technology, diplomatic and military. Today, China is on the threshold of superpower status. Yet, China cannot get into a full-scare war with India on the border. Instead, China will apply strategy of ambiguity through the doctrine of “Creeping Incrementalism and Extended Coercion”, in a more assertive and aggressive manner to keep the border disputes alive to be settled at its terms in posterity when it gains dominant power status ASP.

China perceives potential external security threats on multiple fronts: in the Northeast, over sea frontiers with Japan and South Korea; towards East, over re-unification of Taiwan; and in South China Sea with Philippines, Vietnam and other SE Asian neighbours. On the land borders, the crisis points include: in South with Vietnam; in Tibet with India; and with others in the North. At the same time, China too is facing major internal security challenges like in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. Taiwan is yet another key challenge. Post Covid-19, China too has to emerge from the Great Economic Depression.

Today, China is at an advantage, which it may not like to squander away by one misstep. It has an enduring, multi-dimensional and deep-rooted relationship with Pakistan. Hu Jintao had described the relationship as “higher than the mountains and deeper than oceans”. Pakistanis have added “sweeter than the honey” to it. Xi Jinping refers to Pakistani people as “good friends, good partners and good brothers.” None should forget that China remain beholden to Pakistan for sponsoring Henry Kissinger’s visit in 1970’s from its soil and the “Ping-Pong Diplomacy that followed contributing to China’s rise. According to one of the US declassified documents, “China has provided assistance to Pakistan’s program to develop a nuclear weapon capability in the areas of fissile material production and possibly also in nuclear device design.” And, 80% of Pakistan Armed Forces are equipped with China’s combat systems and also the ongoing China Pakistan Economic Corridor leading the Gwadar Post and route to West Asia. Also, China is also at an advantage in Nepal, Sri Lanka, and has gained strong strategic foot-hold in West Asia and Latin America.

On account of an improved connectivity, infrastructure development and access to the Line of Actual Control (LAC), the depth, frequency and intensity of such face-offs will increase, threatening a fragile peace which exists, with the last shot fired in anger in October 1975. Such incidents and standoffs like the one at Doklam in 2017 or Depsang and Chumar are the ever-present potential drivers of conflict between the two nuclear-armed neighbors — home to one-third of humanity.

Managing contested borders is a continuous costly drain on the armed forces and the ever-depleting defence budget. Once resolved, India will be able to optimize the defence forces, position itself as a military power and focus on the western borders by raising the costs of the proxy war by Pakistan, leading to relative peace.

Some analysts believe that post Covid-19 is an opportunity for India and China to resolve the ‘boundary question’, and seek a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable solution. Such an assumption is excellent if both nations manage their relations on “quid pro quo” basis immediately instead of dilly-dallying for eternity. For doing so, Modi has to forge consensus with the rebellious opposition rivals. At the same time, there is no need for analysts to articulate various war scenarios like whether India will be forced to fight its war alone singlehandedly, or lent diplomatic support by others or provide military combat systems or participate jointly to face China’s military threat.

Viewed in the foregoing, India’s strategic objectives must be to create a new and favourable equilibrium across not only Asia-Pacific region and the Indian Ocean domain, but also on the international plane. Admit all alike that India will not be able to stop every act of aggression by rival powers, but it can significantly raise the costs of such aggression and frustrate whatever strategic goal the aggression intends to achieve in all fields of national security.

Under S Jaishankar, Minister of External Affairs, India’s diplomatic approach is highly imaginative, calculative, deliberate and focused that is assertive and unyielding posture with a prudent recognition that, at times, flexible with adjustments and compromises. For example, if China deliberately provokes a major military confrontation on the LAC along the land borders, then India must make it clear diplomatically that the military escalation would also spill over into the Indian Ocean Region that would have major implications on Chinese oil imports or use of atomic demolition munitions in the disputed areas of the LAC.

To successfully counter the shifts in threat of force, or means of coercion (terrorism, cyber attacks, covert operations, trade wars, political subversion, climate change) to undermine India’s national interests by China, it goes without saying that it must be done from a position of strength from within and not weakness: social unity and quality, political consensus, enhanced economic power, technology parity or superiority and security forces capabilities and effectiveness.

At the political level, Xi Jinping, his Foreign Minister Wang Yi and the present Ambassador in India Sun Weidong gaveindications of a shift in China’s position to resolve the boundary row since March 2013. In public, they have been highlighting the need for an early settlement of the boundary question. Yet, there have been no significant breakthroughs.

If ever there was an opportunity for the two Asian giants to resolve the contested boundary, it was during Deng Xiapao time in mid-1980s, which India squandered. Now, it is too late with China having acquired almost superpower status.

If India wants to remain a sovereign nation, it must develop its power potential in all fields earliest. There is no alternative. After all, “Power respects Power”. China is attempting coercive diplomacy by escalating border tensions. Indian military must boldly counter the Chinese military aggression on the borders. Also, demonstrate its power in the Indian Ocean Region.Also, close the trade with China which favors China.