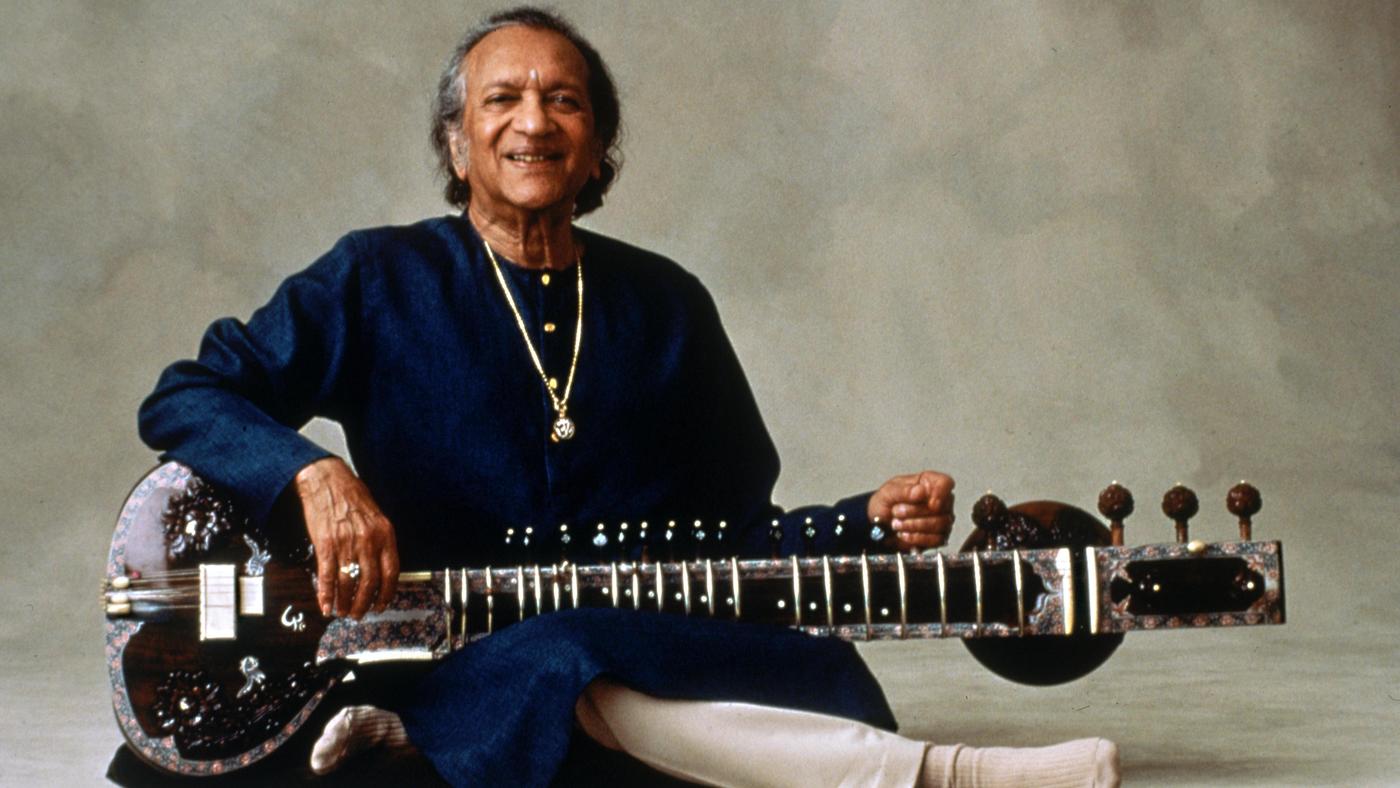

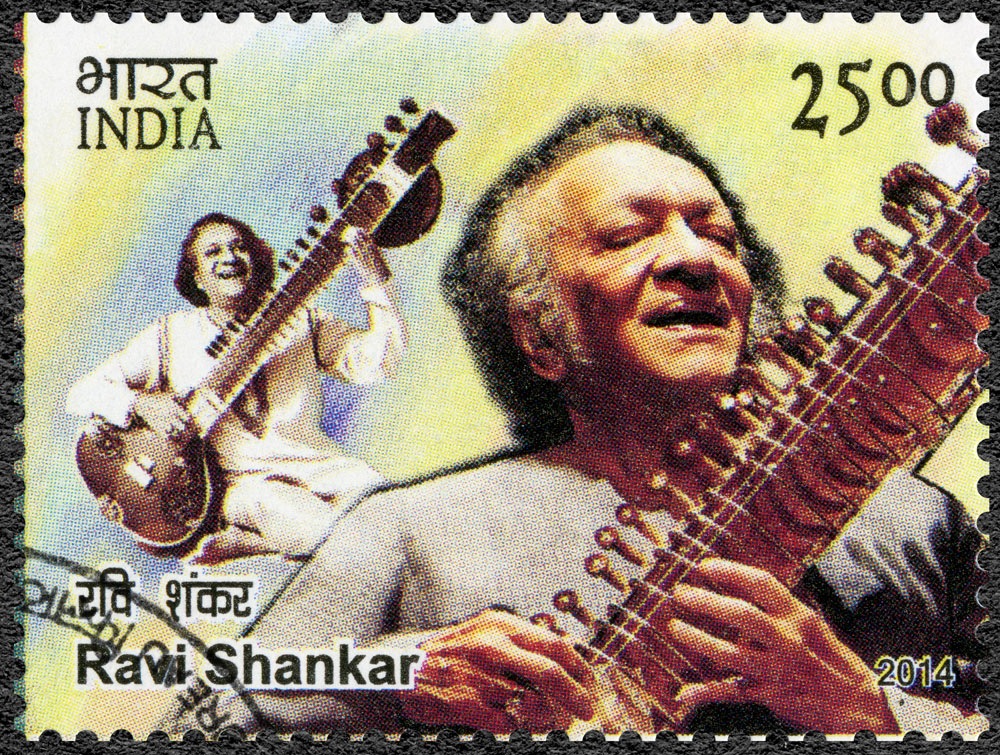

One of the early Indian names on the international music stage, Pandit Ravi Shankar left everyone mesmerized with his consummate skill. Narendra Kusnur sketches his encounters with the maestro

PART 1 – ALAAP

On a January afternoon in 1997, I was suddenly assigned to interview sitar maestro Pandit Ravi Shankar, and rush to his guest house at Napean Sea Road, Mumbai, in two hours. He was to do a concert in Mumbai the next morning, and I had to head back to file my article.

I was nervous and scared. Though I had met classical musicians before, I had never interviewed someone of his stature. The closest had been to ask vocalist Pandit Bhimsen Joshi one question at a crowded press conference. I had heard Shankar’s records, loved his music in ‘Anuradha’ and ‘Gandhi’, known of his association with the Beatles and Woodstock, and even attended one concert in New Delhi, but I didn’t have any in-depth information on him. The word ‘Google’ didn’t exist then. Plus there was the deadline.

My colleague, photographer Prashant Nakwe, and I reached the venue on time. We waited in the drawing-room, and despite the air-conditioning and agarbatti aroma, I was sweating and shaking. Shankar suddenly walked in, folded his hands to indicate namaste, flashed a smile and sat down next to me. He had a buoyancy that disguised his 77 years. I addressed him as Panditji and he said, “Call me Ravi”. Of course, I settled for ‘Raviji’ but suddenly remembered I forgot to touch his feet.

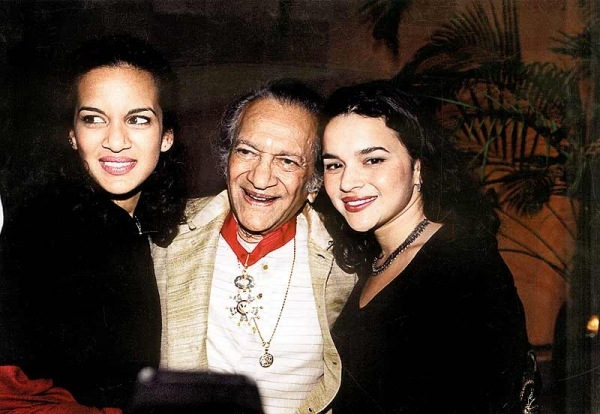

The musician introduced the two ladies who joined him. “This is my wife Sukanya and this is my daughter Anoushka,” he said, as Nakwe clicked away. He was talking to me and posing for the camera at the same time, without ignoring either of us. Probably noticing I was in my early or mid-30s, he began talking about the Beatles, even making me hum a few songs. Before I realized it, he was speaking on Indian classical music in a language I understood. The rest of our conversation flowed like a river.

PART 2 – JOD

December 11 marked his seventh death anniversary. Over the years, there had been some wonderful interactions. I interviewed Shankar in person on four subsequent occasions, spoke to him over the telephone once and met him a few times at concerts or dinners. Naturally, I was bowled over by his sheer charisma and conversational skills each time. There was melody in those eyes, magic on his tongue. That first meeting also set the tone for understanding his music and becoming an ardent fan.

A representative of the Maihar Gharana, Shankar learned from legendary multi-instrumentalist Baba Alauddin Khan. Earlier, he had a chance to accompany his brother, dancer and choreographer Uday Shankar, in Paris. This was where he was first exposed to western culture.

Shankar married Khan’s daughter, surbahar exponent Annapurna Devi, and they eventually separated. In the 1950s, he traveled extensively to the US with tabla players Pandit Chatur Lal and Ustad Allarakha. The latter also accompanied him at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967 and Woodstock Festival in 1969. By collaborating with violinist Yehudi Menuhin, composer Philip Glass, flutist Jean Pierre Rampal, cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, and conductors Andre Previn and Mumbai-born Zubin Mehta, he attracted more foreigners to Indian music.

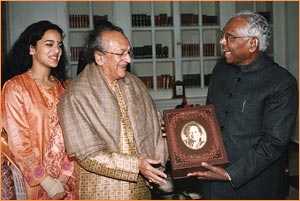

The doyen was conferred the Bharat Ratna in 1999. He had come on a personal visit and stayed at the Hotel Oberoi, now Trident. Anoushka was 17 years old then and had made a small name for herself, though cynics felt she was only riding on her father’s glory. I was to interview them separately, and he had a vague recollection of our first encounter.

My talk with Shankar was more musical this time. I had heard quite a few of his recordings by then, and my favorites included raags Hameer, Jogeshwari, Kirwani, Charukeshi, Maanj Khamaj, and Miyan Ki Malhar. Without getting technical, he explained the compositions briefly. I had also admired his album ‘Chants Of India’, produced by George Harrison of the Beatles and released in India by Milestone Entertainment. The reference led to a talk on the spiritual nature of Indian classical music.

The interview over, I took out a Saregama HMV album called ‘Milestones’, for Shankar to autograph. Sukanya had not seen the cover before and felt it was the repackaged version of an older recording, released without telling them. She felt he shouldn’t sign it, but he calmly obliged, saying, “It’s not his fault. We can get this copy in a music store and approach the label.”

A few weeks later, Shankar returned to Mumbai. Since I was on leave, I decided not to attend his press conference. My son was born on March 12, 1999, the day the event was scheduled. I called up my office to inform them when I got the news that Menuhin had passed away. A few hours later, I was on my way to The Oberoi to get his personal tribute to the great violinist.

Though he was in a rather somber mood, Shankar congratulated me on my son’s birth and told his manager Terry to give me a box of sweets. He spoke at length about Menuhin’s love for India, how he encouraged him to perform in the US, and their 1967 collaboration West Meets East.

By then, I had realized that I had slowly built up a collection of Ravi Shankar cassettes, many of which I eventually bought on CD. There were jugalbandis with sarod maestro Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, his sitar concertos conducted by Previn and Mehta, and recordings of lesser-known compositions in raags Asa Bhairavi, Bhinna Shadja, and Pancham Se Gara. I also followed sitar maestros Ustad Vilayat Khan, Pandit Nikhil Banerjee, Ustad Abdul Halim Jaffer Khan, and Ustad Rais Khan. The choice of listening would often depend on the mood and the preferred raag. Late at night, it often had to be Rais Khan’s Darbari.

One of the most memorable moments was attending the Gunidas Sangeet Sammelan in 2002, where Shankar played Raag Hameer Kalyan in a 10-and-a-half beat cycle. Percussionist Taufiq Qureshi and flutist Ronu Majumdar were sitting near me, and they just couldn’t believe what a phenomenal performance he gave at the age of 82. For the interview, to avoid any doubts, I made sure I carried CDs released by tabla maestro Ustad Zakir Hussain’s Moment Records.

Those days, when there were no selfies, getting an autograph had a special charm. So on my next interview, I carried a copy of Shankar’s book ‘Raga Mala’. Reading it was an eye-opener as it contained some magnificent anecdotes and lots of information on his musical thinking. During the interview, he elaborated on some things the book covered. It was to be my last in-depth interview of him, though we interacted a few more times.

When Ustad Vilayat Khan passed away in March 2004, I called up Shankar in New Delhi for a short tribute. Considering the talk of their famous rivalry, I did not expect him to say much. But he spoke at length, describing Khan as a precious gem and a soulful artiste. He said stories of the rivalry were created by the Press and by those with vested interests. “We had some differences over technical musical matters, but as artistes, we admired each other,” he said.

I met Shankar twice after that. One was at a dinner hosted to honor Zubin Mehta at the Taj Mahal hotel, and early 2005, at a New Delhi concert featuring violinist L. Subramaniam, vocalist Al Jarreau, and keyboardist George Duke. On both occasions, he spent a few minutes with me, cracking a joke or two. Sukanya would be with him everywhere.

Though I wanted to meet the maestro again, it never happened. He spent a lot of time between the US and New Delhi, and his visits to Mumbai reduced drastically. I meanwhile discovered some rare footage on YouTube, including this amazing clip of him rendering Raag Pancham Se Gara with Allarakha at Monterey, and one where he conducted an orchestral session featuring Allarakha, santoor maestro Pandit Shivkumar Sharma and flutist Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia.

Shankar’s death on December 11, 2012, was a huge loss to not only Indian music but world music too. At one of his press conferences, a journalist had asked him how he felt to be described as the godfather of world music. He had replied, “Whatever that means, I don’t look like Marlon Brando from any angle.”

Millions have enjoyed and appreciated Shankar’s music. But for those who got to know him even a bit, his charm and humor were enduring. The term ‘magnetic personality’ was probably created for him.