As the lamp is lit to mark the inauguration of the Prithvi Theatre Festival on November 3, it also commemorates the birth anniversary of Prithviraj Kapoor, after whom the iconic theatre is named.

Prithviraj Kapoor or Papaji as he was affectionately called, not just founded a film dynasty (to which a great number of film industry people are linked by blood or marriage, and a new member has just been added, as great grandson Ranbir Kapoor and his wife Alia Bhatt become parents), he dedicated the best years of his life to theatre. Along with working in films to fund his productions, for 16 years, his touring repertory company Prithvi Theatres covered the length and breadth of India, taking socially relevant plays to the people. It was his dream to have a permanent home for his Prithvi Theatres. Five years after his demise, with Shashi Kapoor’s effort and Jennifer Kapoor’s gentle guidance, Prithvi Theatre came into existence and helped initiate and nourish a Hindi theatre movement in Mumbai.

The story of that eventful life began in Peshawar in 1906, and the seeds of an acting career sown by a professor of dramatics at Edwards College, who spotted talent, and cast the young Prithviraj in his plays. By the time he was 17, he was married as was the custom in those days, and by the time he mustered up the courage to defy his father– who thought actors were disreputable– and travel to Bombay (now Mumbai), he was the father of three children, the oldest being Raj Kapoor.

The beginnings of that magnificent career were in 1928, when the 21-year-old got off the Frontier Mail that had carried him from Peshawar to Mumbai. He had a suitcase in one hand and his lucky hockey stick in the other. He hailed a Victoria to the Gateway of India, looked at the sea, then raising his face to the skies said, “Mr God, if you don’t make me an actor and a star here, I will swim the seven seas and go to Hollywood.”

Those were the days when Mumbai was truly the city of dreams– though the gates of a fledgling show business did not open for everybody, they did not rudely slam on the face of an outsider either, especially not one as handsome as Prithviraj Kapoor.

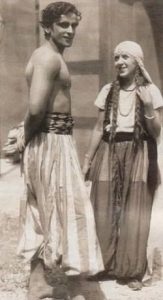

He made his way to Ardeshir Irani’s Imperial Studio, where the Pathan guard let him in, because he spoke his language, Pushto. The guard also advised him kindly to go home, the movie industry was not a nice place, but giving up was not an option. Then there is the saying about fortune favouring the brave. Which is how on his first day in Bombay (now Mumbai), the young man found himself in the line of extras, who were picked by production assistants for the day’s shoot for a daily wage of Rs 2.50. On the third day, the main actor of the under-production Cinema Girl played truant, the furious director asked the leading lady Ermeline to select a hero from among the hopefuls who had congregated that day, and the tall Greek God was just right to be a hero.

After getting that lucky break, he did several films, including India’s first talkie Alam Ara (1931). The transition from silent films to talkies was difficult for most actors who had weak voices. Because of his theatre training, Prithviraj Kapoor had a strong voice and fine diction, so had no problem switching to talkies.

Despite the success of his films, he was restless for more realistic roles over the bombastic costume dramas popular then, and he found what he was looking for in the Grant Anderson Theatre Company, with the English actor-manager, who came to India and wanted to work with local actors. When the Company reached Calcutta (now Kolkata) in 1932, it shut down. For a star actor like Prithviraj, there was no dearth of opportunities. He was snapped up by New Theatres and acted in films like Seeta, President and Vidyapati, now considered classics.

After seven years in Calcutta, the family, with the addition of more children, Urmila, Shammi and Shashi returned to Bombay. In those days, stars worked with studios on a salary; he was the first to break out of the restrictive system and went freelance. By then, he was a major star, so there was no resistance.

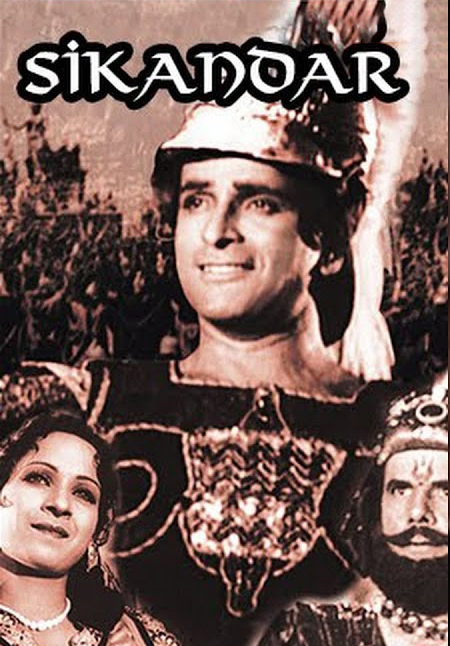

The biggest film of his career till then was released in 1941—Sohrab Modi’s Sikander, in which he played Alexander The Great, with Modi playing King Porus. With the single-minded dedication he was known for, he sent his family to Peshawar for three months and worked on building his physique and fleshing out the character in his mind. By the time the film went on the floors, he ‘became’ Alexander The Great, so much so that history textbooks used his photograph to portray the Greek emperor.

It was at the peak of his film career, that he heard the call of theatre again. This time, he set up his own company—in January 15, 1944, Prithvi Theatres was established, with a havan. The first production was Shakuntala. So many talented people joined the theatre caravan with Papaji, so many careers took off, and so many bonds were formed for life. If listed, the thread of connections would run into several miles.

The 19-year-old Raj Kapoor was stage manager, and in charge of costumes, lights, sets, make-up, sound. Three people came from Hyderabad to audition and join up—Satyanaryan went on to become a famous choreographer, Hemavati, who later married actor Sapru, and Shankar, who teamed up with Jaikishen for a successful and long-running musical partnership. Uzra Mumtaz, sister of Zohra Segal, was cast as Shakuntala, opposite Prithiviraj himself playing King Dushyant. Shammi and later Shashi played the role of the young Bharat.

Shakuntala was an expensive production, and lost money even after it did well. Also Papaji was generous to a fault, and helped out anybody who approached him, emptying out his pockets without a second thought for anyone in need. A whole bunch of relatives and friends joined Prithvi Theatres, and later built their careers in films—he never stopped anyone who wanted to leave. He would joke, then when they flew high, they could give him a lift!

Geoffrey Kendal, who ran his own theatre company Shakespearana with his wife Laura (their daughter Jennifer later married Shashi Kapoor), wrote about Papaji in his book, The Shakespearewallahs, “He loved it all—being a father figure, a great actor, the idol of all and sundry. He did everything in a big way and he acted all the time, on stage and off, but he was genuinely good-hearted and unbelievably kind to his company. He spent much of what he earned in films to keep his theatre troupe together out of charity.”

Prithvi Theatres was the first professional Hindi theatre repertory company in India then—there were folk troupes and some Parsi Theatre, and many amateur hobby groups. He introduced a naturalistic style of acting and broke the conventions of popular theatre prevalent then.

After Shankuntala, he decided to commission original plays that were socially relevant and realistic—Deewar (1945), Pathan (1947), Ghaddar (1948), Ahooti (1949), Kalakar (1951), Paisa (1956). They had themes like communal harmony, national unity, rural reform, and women’s issues.

The strength of the touring company varied from 100-150 and it was completely self-sufficient. He insisted on discipline and a strict rehearsal schedule; he played the leads, but all other actors were treated alike. They learnt all the lines, and an actor playing a hero in one show could play a bit part in the next and vice versa. He did try to hire an understudy, but nobody could command the stage like he did, and audiences wanted to see him.

For tours, a third class bogey was booked and everybody travelled together. They carried their hold-alls and if better accommodation was not available, they slept on the floor in lodges or makeshift spaces. The cooks travelled with them and they all ate the same food. He wore only cotton or khadi. He was a star, he need not have lived with such austerity, but he did. “We are not landowners,” he used to say, “We are labourers.” He imposed a fine of one anna on anyone who stood up when he walked into the rehearsal space.

The troupe travelled to cities and small towns all over the country, performing in cinema halls or informal venues, which the in-house carpenters modified before the performance. That is why it was his dream to have proper theatres in the country.

Today, it is impossible to imagine the passion and idealism of one man to create, lead and perform on stage under all conditions. The plays they did must have influenced audiences and softened a lot of hardened hearts in those post-Independence, post Partition days.

By the late 1950s, Prithviraj Kapoor had started losing his voice—sixteen years of strain on the vocal cords, he acted on stage without mikes, and did a lot of public speaking too. In May 1960, he had to regretfully shut down Prithvi Theatres. He hoped to have a home for his theatre company one day, a theatre of their own—which Shashi and Jennifer Kendal fulfilled, unfortunately after he passed away but his dream lives on.

In 1960, he played another great role in a historical—Akbar in the K.Asif masterpiece, Mughal-e-Azam. It remains one of his finest, his regal stance and speech imitated everytime an actor played a Mughal royal. He carried on acting in films—including his grandson Randhir Kapoor’s debut Kal Aaj Aur Kal (1971). Around this time he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Disease and passed away a year later in 1972.

When asked why he had named his troupe Prithvi Theatres, in the plural, he had replied that it was because he hoped there would be a theatre in every town in India.

The one in Mumbai, now being managed by his grandson, Kunal Kapoor, has kept the city’s theatre talent going for 44 years, by simply being a well-equipped, smoothly run, warm and welcoming space for performance and audiences alike. Imagine if, as Prithviraj Kapoor had envisioned, there had been one in every town, how much more talent would have been discovered and nurtured.