The memories of “those were the days” sustain and nourish us as we navigate the labyrinths of adulthood, writes Vandana Kanoria

Skirts were mini and sideburns were long. Men’s fashion was safari suits, a wholly indigenous fashion invention, accompanied by that dreadful accessory, the pouch.

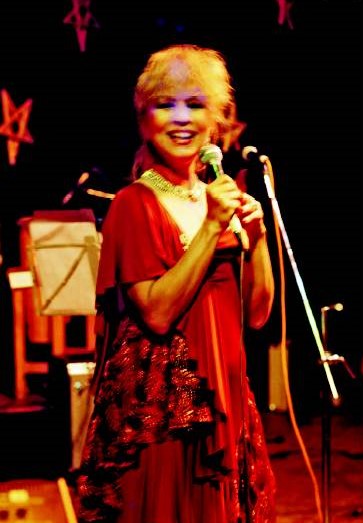

Toothpaste was Bianca, with those little animal collectibles, and soap was Cinthol. Magazines were Life and Chandamama; Beatles and Mary Quant were the rage and Air India and BOAC ruled the skies. Bangladesh was still East Pakistan, and a gungi gudiya discovered her iron fist. We saw the hippie movement spreading and Neil Armstrong landing on the moon. Pam Crain crooned the nights away in hip and happening restaurants in cities that no longer exist as we knew them. She would set the nights on fire during the swinging 60s and 70s when Calcutta was the mecca of all that was swish and posh and where life was an endless party.

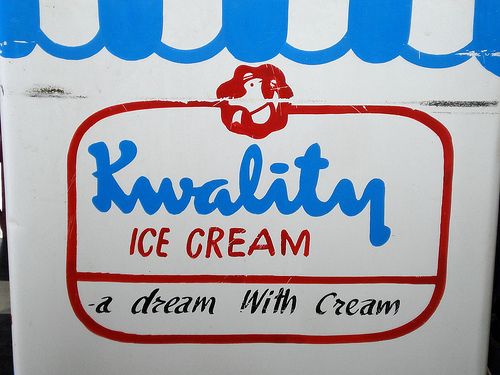

Most of our memories are not stored in photos, but in tastes and smells. After all, Proust wrote a huge tome, sparked by a nostalgic incident of memory of the taste of a madeleine cake dipped in tea, which he remembered having as a child. With chocolates and ice creams in hundreds of flavours and varieties today, enticing you on Instagram and WhatsApp, it is hard to imagine the joy Cadbury chocolate, Gems, and Nutties held for those growing up in the sixties. Everyone eagerly looked forward to birthdays when two éclairs per child, or a small packet of Nutties were distributed to the whole class. Kwality was synonymous with ice cream and the ice cream man in his blue uniform and cap would pass by, wheeling his blue and white cart ringing his bell. Like the Pied Piper he drew the children to him who crowded his cart clamouring for their share of goodies. He would also be at school where, for a princely sum of 60paise you could buy the most expensive ice cream – the choc-bar! We, with our measly pocket money of 1rupee twice in a month could rarely afford such delicacies. No ice cream since, has tasted so heavenly as the humble choc-bar. Of course, there was Kwality’s poor cousin Magnolia, the cart painted in lurid orange. But all of us, friends and cousins alike, turned up our noses at it. Nothing ever came close to Kwality.

Sometime in the same period, we heard the twang of a very heavy string in the street. It was the dhunia– the cotton beater – who usually appeared when the rains slowly melted into a slight chill in the evenings. Quilts were taken out for winter. Under the eagle eye of mums and aunts, the cotton was beaten, re-fluffed and stuffed back in the quilts. Presiding over the whole exercise was the all-important Kallu darzi, who with his noisy, whirring sewing machine sewed back the newly filled quilts.

Then there was this strange gentleman called the Phitawalla- we never learned his name – purveyor of “imported” goods. In his crisp white pyjama and a white shirt he would arrive at my nani’s house, carrying an Aladdin’s cave in his numerous boxes. Out came colourful ribbons, delicate lacy handkerchiefs, brightly coloured hair pins – one style called ‘Love in Tokyo’ for reasons I have never been able to fathom. Good natured bargaining and haggling went on and at end of it, both went away happy- we with our little packets of baubles and buttons and Mr. Phitawalla with all that he had sold.

An old bent and really shrivelled gentleman used to come home once a month lugging a huge parcel tied in cloth and carrying a battered suitcase. Out tumbled books in Hindi. He was the famous Kitabwalla who went to homes to sell books to ladies who loved reading, I remember my Mum and my aunt, Bari Ma spending many animated hours discussing books, the must reads, what everyone else was reading and the merits of little known gems. The conversation would end with a large pile of books bought, which Mum and Bari Ma would divide in half, read their pile and exchange them with each other. For days after the kitabwalla came the two could be found hiding from the rest of a large, unwieldy family, sipping cups of tea reading and discussing the new books.

When the Akashvani jingle, based on raag Shivranjani, played you knew dawn had broken. More than a source of entertainment the radio was an integral part of our lives. No evening was complete without filmi songs on Vividh Bharti and Sundays without the popular western music programme Musical Bandbox, where boyfriends and girlfriends would send messages to each other through songs under the parental radar. But nothing ever came close to Radio Ceylon’s iconic and universally loved Binaca Geetmala. Amin Sayani’s baritone hooked us and held us spellbound. It featured ‘what’s trending this week’. Such was the popularity that we wrote lists of songs in case a friend had missed an episode.

When the Akashvani jingle, based on raag Shivranjani, played you knew dawn had broken. More than a source of entertainment the radio was an integral part of our lives. No evening was complete without filmi songs on Vividh Bharti and Sundays without the popular western music programme Musical Bandbox, where boyfriends and girlfriends would send messages to each other through songs under the parental radar. But nothing ever came close to Radio Ceylon’s iconic and universally loved Binaca Geetmala. Amin Sayani’s baritone hooked us and held us spellbound. It featured ‘what’s trending this week’. Such was the popularity that we wrote lists of songs in case a friend had missed an episode.

An endless collection of vinyl and cassettes and tape-recorders were necessary possessions of a music enthusiast back then and much time was spent on fixing and untangling our tapes using a pen or pencil. There’s just something about being able to hold an album sleeve and admire the glorious graphics on them, that made the whole music-listening experience feel more special.

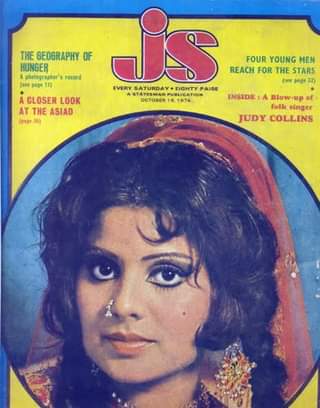

But what really defined growing up in the 70’s for me, was Junior Statesman. Popularly known as JS. Started by that ultimate renaissance man, Desmond Doig, for the “hipster urban youth”. “The air of frivolity was all-pervasive”, Siddharth Bhatia wrote of the magazine. “It seemed as if not just the readers but also the writers were out to have fun.” The magazines were full of interviews with popular musicians and actors, reviews of the latest Indian and Western albums, posters of celebrities, and fashion advice (“Tear A Maxi Into Mini In Seconds”).1960s Kolkata was a politically turbulent city. There were the beginnings of the Naxalite movement, an ongoing insurgency between the radical left and the Indian government, labour strikes and protests by student unions. JS was a handbook on what to wear, what to talk about, what to do, and what to listen to. It was fresh, intelligent, funny, and bold. The magazine also featured crosswords, comic strips and short stories, weekly horoscopes, sports news and a popular column called ‘Rear Window’ written by Jug Suraiya. These were thought pieces “with discussions on Sartre, Nietzsche and others, but told in Jug’s inimitable way,” When it was forced to close down, we all mourned the passing of that bright and shining moment—the crumbling of a dream.

But what really defined growing up in the 70’s for me, was Junior Statesman. Popularly known as JS. Started by that ultimate renaissance man, Desmond Doig, for the “hipster urban youth”. “The air of frivolity was all-pervasive”, Siddharth Bhatia wrote of the magazine. “It seemed as if not just the readers but also the writers were out to have fun.” The magazines were full of interviews with popular musicians and actors, reviews of the latest Indian and Western albums, posters of celebrities, and fashion advice (“Tear A Maxi Into Mini In Seconds”).1960s Kolkata was a politically turbulent city. There were the beginnings of the Naxalite movement, an ongoing insurgency between the radical left and the Indian government, labour strikes and protests by student unions. JS was a handbook on what to wear, what to talk about, what to do, and what to listen to. It was fresh, intelligent, funny, and bold. The magazine also featured crosswords, comic strips and short stories, weekly horoscopes, sports news and a popular column called ‘Rear Window’ written by Jug Suraiya. These were thought pieces “with discussions on Sartre, Nietzsche and others, but told in Jug’s inimitable way,” When it was forced to close down, we all mourned the passing of that bright and shining moment—the crumbling of a dream.

Somewhere between chatting on a rotary phone with a cord that could only be stretched so far, and mobile phones that could travel to all corners of the earth, we grew up. We grew up in an age of transition, from hand written letters to texts on the phone. Time paused and we thought we were the masters of the universe. But technology changed all that. Now there is no little old lady selling red ber sprinkled with salt on the street corner. The tamarind on the tree waits forlornly for children to pluck it off. And yet, we exist in all these little moments. The memories of “those were the days” sustain and nourish us as we navigate the labyrinths of adulthood.

Comments are closed.