Ayaz Memon looks back at the historic World Cup that he witnessed, which transformed the world of cricket for India.

When Kabir Khan announced that he was making a film on India’s 1983 World Cup victory, I was both overjoyed and assailed by apprehension.

The sport was getting greater recognition in India, including finding celluloid expression (flicks on Milkha Singh and MC Mary Kom had come earlier), which was a splendid improvement from the past. But how India’s greatest cricketing achievement (yet) would be treated was a concern.

Would this be a true-to-life account of the magnificent campaign, which saw Kapil Dev’s team pull off arguably the most stunning victory in the history of the game? Or, as happens often in Bollywood, history would be contrived and fictionalised to the extent that an extraordinary achievement is reduced to farce?

In a meeting with Kabir more than a year ago, when he was trying to fill in gaps in information, there was a feeling of reassurance. His passion for cricket was apparent, and he averred he wanted to stick as close as possible to how the tournament factually

Kabir had also roped in most members of that 1983 World Cup as advisors and mentors, which is important in a project of this nature. For these players, memories of that tournament will never fade. With the passage of time, they also have a better perspective, which can add great value to the film.

I have no idea how the film has shaped up. I hope it does justice to the astonishing achievement of `Kapil’s Devils’, as the Indian team got to be known after the victory. I also hope that Kabir has been able to juxtapose the cricket with the ethos of that era. For, 1983 was a vastly different world from the one we live in today.

Airfare to England, for instance, was roughly around Rs 9000 (economy), the pound sterling’s value was around Rs 21, bell-bottoms and sideburns were in fashion for men, the Cold War had not yet been resolved, the USSR was still intact, there were two Germanys.

And yes, India was the dull dogs of international cricket.

In the two previous editions of the World Cup, 1975 and 1979, India’s had been undistinguished. Okay, let me say it without compunction: India’s performances had been forgettable, dismaying, dismal.

Sunil Gavaskar’s infamous ‘crawl’ of making 36 not out in 60 overs against England in the first tournament in 1975 was universally castigated as going against the spirit of limited-overs cricket. India failed to win any match in that edition.

In 1979, there was a solitary win, but it came against lowly East Africa, so hard to be savored. All other matches all lost, including against Sri Lanka, not full members of the ICC till then. That was the backdrop against which India’s 1983 campaign began.

You might then ask why any sensible Indian would be excited about the 1983 tournament, given that the prospects of Kapil Dev and his team looked hopeless. But that is ignoring the passion for cricket in the Indian psyche – fan, aficionado, journalist.

At that point in time, approaching mid-1983, I was on the horns of a dilemma. Should I pursue law as a profession, or journalism, which I had literally strayed into because of my love for the sport, especially cricket?

Making this choice was agonizing. But whatever the decision, I committed myself to cover the 1983 World Cup in deference to what cricket had meant to me in life.

Frugal resources

With frugal resources – since news organizations, those days hardly spent money on sports events – I flew to England on the eve of the tournament with a couple of journalists from Bombay. In fact there were to be only six journalists from India covering the tournament.

This is important to get a perspective on how cricket coverage in the country has grown since. For instance, for the 2019 World Cup (again in England), there were around 50-55 reporters/writers present. This swelled to almost double the number for the marquee match against Pakistan!

Money was limited. The World Cup was a long-drawn tournament so every penny was crucial. But this was my also first visit to England, and there was so much to see and experience which had otherwise only been read of or imagined.

From London’s superb underground rail system, machines which dispensed chocolates on railway platforms, various county grounds which bespoke deeds of the some of the greatest names in the game, the sights and sounds of Soho and Southall et al, the picture-postcard countryside as one traveled by British Rail, all made for a memorable experience.

But the primary reason for being in England was the World Cup. When I was on the flight, I spent the 9-9.5 hours mulling about India’s prospects, discussing with the two journalists traveling together whether there would be any improvement over the previous two tournaments.

I didn’t think so, which is why I chose not to see India’s first match at Old Trafford against West Indies and opted for England versus New Zealand at the Oval instead. There were three reasons that influenced my decision, two of them related.

Essentially, what hope does India have against the reigning champions, I asked myself? None at all was the answer. So why incur the expense of traveling to Manchester and why not watch a match in London, which was based, instead?

Also, I was very keen to watch New Zealand’s rising star, batsman Martin Crowe, of whom I had heard so much. And their match was to be played at the Oval, which was my favorite ground (though I had never seen it earlier) ever since B S Chandrashekhar’s team had helped India win a Test series in England for the first time, in 1971.

As it happened, what looked like an eminently sensible decision turned out to be totally wrong. While I was watching England v New Zealand at the Oval, India was pulling off an upset win over West Indies.

Because of rain, that match spilled over into the second day for a bit, but the West Indies had to bite the dust, which caused bookmakers to issue a hasty revision of odds. West Indies still remained favorites, but India, 66-1 at the start of the tournament, had odds against the hastily revised.

Once bitten twice shy, I eschewed any further adventurism where match coverage was concerned, following the Indian team diligently for their remaining matches in the league phase though there was nothing exceptional to report.

After the big upset in the first match, India seemed to have slumped into a familiar rut, losing match after match, except the first one against Zimbabwe. This was a double leg, two-group tournament, in which each team in in the same group played the other teams twice.

Matters reached crunch situation by the time India met Zimbabwe again for the second match, at Tunbridge Wells. A defeat here would virtually terminate the team’s campaign. There was more trepidation than hope when the team left for the small town in Kent County.

Historic contest

Though India had beaten Zimbabwe earlier, the team was no pushover, boasting several high-quality players in Duncan Fletcher, John Traicos, Dave Houghton, and fast bowlers Kevin Curran and Peter Rawson. In fact, in their first match of the tournament, Zimbabwe had beaten Australia.

The contest turned out to be historic. To save money on lodging in Tunbridge Wells, I travelled there from London (where I had a place) on the morning of the match. To save even more money, I took an off-peak ticket, which brought me to the ground about half an hour after the scheduled start.

There was a hush when I walked into Nevill Ground. The dressing rooms were on the way from the gate to one of the shamianas that was the press enclosure for the day. The small ground was packed, but there wasn’t the clamour one would associate with an ODI match.

Seeing former India great Gundappa Vishwanath standing in the porch of the Indian dressing room, I ventured there to get an update from him on what was happening in the match.

This would be unthinkable today when players’ enclosures are so strictly sanitized. But as mentioned at the start, 1983 was a world apart from the one we live in, particularly in sport.

I sidled up to Vishy and asked him how the match was progressing. “All fine, nothing to worry,’’ he replied. Not having taken a look at the scoreboard till then, I turned to it and was shocked. 9-4! India’s top order had been lopped off and the team was in deep crisis.

This soon became 17-5 as another wicket fell. Then started the astounding recovery. Kapil Dev got into his groove with a couple of reassuring boundaries, found an ally in Roger Binny, and the Indian innings got the kiss of life.

I must have watched the match with Vishy for around 25-30 mins, and as soon as explosive strokes started emanating from Kapil’s bat, like ack-ack firing from a machine gun, I sense we were watching something sensational and swiftly headed towards the press shamiana.

Finding a strong ally in Syed Kirmani, Kapil scored a blazing 175 not out to take India to 262, which turned out to be a match-winning score. I rate this still as the best ever innings in a one-day international.

Incredible impact

A number of batsmen have far exceeded Kapil’s, some even making double hundreds. But considering the hardship quotient for Kapil, they all fall short in terms of impact on match and tournament. Remember, he was not a specialist batsman and India were in a hopeless situation when he came out to bat.

Sadly, Kapil’s brilliant knock was not captured for posterity, either on radio or TV. The BBC was on strike for just that day, and one of the greatest exhibitions of batting was limited to being disseminated by newspapers or conversations.

I must confess that this kind of helped me in subsequent years. As the stock of Indian cricket grew, that knock acquired greater sentimental value. As one of the few eyewitnesses to that inning, there has been a recurring demand for a piece, debate or discussion in the 37 years since!

Victory over Zimbabwe seemed to bring new zeal in the team. The pressure under which this was achieved injected self-belief, and a deep desire to win had been stoked. The players had a spring in their steps as they moved ahead in the tournament.

Australia was summarily swept aside to complete the league phase and qualify for the semi-final. This was against the home team and joint favorite England. The match at Old Trafford was tantalizing, with India prevailing through a fantastic all-round show.

My abiding memory of that match was a placard in the stands that read, “Kapil Eats Botham For Breakfast.’’ The two great allrounders were always vying for honors when they competed against each other, but this time it was clear who had come out on top.

India was now in the final. Unbelievable but true. By now, people of Indian origin in England had been roused into a frenzy. Crowds at the semi-final resembled what one would see in Bombay or Calcutta. It was the same at Lord’s on June 25, 1983, when Kapil’s team met the mighty West Indies.

I reached late for this match too, though not in trying to save money: In fact to the contrary. Having overslept a bit, I thought I’d take a cab to the Lord’s instead of changing going by underground rail since this entailed changing a couple of lines. The cab cost a bomb and also highlighted that the efficacy of the underground rail in London was unchallenged.

Rushing past Grace Gates, I heard a roar and someone yelling “Gavaskar is out.’’ The Stewards were stodgy, not appreciating my haste. A couple of days earlier, when I had gone to collect my accreditation for the final, one had said to another, “Now we have Gandhi coming to Lord’s’’’’.

This was obviously inspired by the huge success of Sir Richard Attenborough’s film which made the Mahatma a household name in the western world but was nonetheless condescending. I asked them curtly to hurry up since I was losing vital minutes of the match.

Running up the staircase to the press box, I met former Australian captain and commentator Richie Benaud. “Odds of 66-1 still if you want to bet on India,’’ he said smilingly. I was tempted fleetingly.

But not being a gambling man, and the fact that the opponents were West Indies, I smiled back in return and ran past him. By the time the Indian innings ended, I admired my own smartness at not having taken the wager. India was bowled out for a very modest 183. Well done in reaching this far, but surely the trophy winners will be West Indies.

never be the same again

Twice champion with an array of devastating batsmen, there seemed no way India could win. Not even when Balwinder Sandhu got Gordon Greenidge early with a banana inswinger.

Greenidge was replaced by ‘Boss’ Viv Richards who looked in a mean mood and from the manner in which he started hitting boundaries all around, it appeared the match would be over in double-quick time. Then, against the run of play, came the turning point.

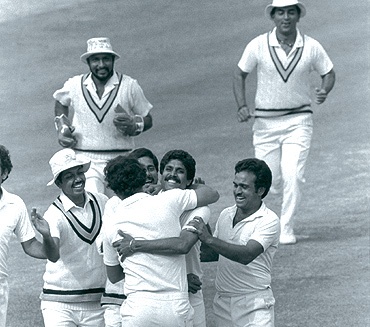

Richards tried to hit Madan Lal out of the ground, skied the ball to deep mid-wicket where Kapil Dev, running backward almost 20-25 yards, took a fantastic catch. This was just the inspiration the Indian team needed.

With Richards gone, the West Indies started struggling. Wickets began falling regularly, leading to a collapse that was totally unexpected: by cricket fans anywhere, the West Indies team, and I dare say, the Indian team too.

When the last wicket fell, the crowd, largely India, erupted. Dhols came out, and groups doing the bhangra took over the Lord’s ground to honor the Indian team in the dressing room balcony.

India had turned the world upside down. Cricket was never going to be the same again. Not in India, not anywhere else.

Good work

Good work

Good article

Keep up

Very nice description of a great historic occasion

nothing new in the story. infact we won against east africa in 1975 world cup, not in 1979. glaring mistake from such a veteran cricket fan?

Great Article Sir. Entire worldcup coverage reminded me of those days when India entered semifinal and with confidence of win, we had all arrangements of grand procession in streets which lasted whole night. i was 14.

Comments are closed.