Filmmaker Sandip Ray tracks back to his father, the legendary Satyajit Ray. By Shoma A Chatterji

The Scenario

Satyajit Ray shifted from the 3, Lake Temple Road residence to 1/1 Bishop Lefroy off Lee Road in 1970 with his wife Bijoya, son Sandip and Ray’s mother-in-law who lived with the family. Ray lived here till his passing away in 1992. He got so attached to this place that he never moved on. Sandip Ray still lives here with his wife Lalita and son Souradeep. One should not forget the beautiful garden we encounter in the long corridor at the entrance leading to the historic study of Ray where some of the world’s best films took birth, and memories, precious memories, that float around like soft, feathery touches caressing Sandip’s mind, refusing to go away.

It is a beautiful colonial building, now a heritage site for tourists lined with so much greenery that it stands out in a city with multistoried buildings and skyscrapers each one looking like the next. It is a batch of flats each has an ornate entry with a flight of stairs framed in grilled iron welcoming you. It earlier housed the Russian Consulate and was called Calcutta Mansion. The name of the road has been changed to Satyajit Ray Dharani in March 2016. Sandip did not like this because it had already been renamed OC Ganguly Sarani after a famous celebrity some time ago and changing it again would be an insult to the memory of OC Ganguly. But the change did take place. All of us, including the present Rays, still refer to it as Lee Road or 1/1 Bishop Lefroy. “I was barely seven years old then and as far as my memory goes, this has been my home all my life,” says Sandip.

The Son – Now

It may appear tough being the only child of one of the world’s best filmmakers in the history of cinema. But Sandip Ray seems unfazed as the son of Satyajit Ray. He comes across as a very grounded and unassuming human being, warm to a fault and a very good conversationalist. I have been to this home several times, twice when Ray was alive and a few times after he had passed away. The house has remained more or less the same with Ray’s study one feels a bit diffident to step into.

“I enjoyed the lockdown during Covid because for the first time in my life, I decided to clean up and reorganise my father’s study which I had not dared to touch before as it is flooded with everything he worked on and with – books, manuscripts, drawings, sketches, musical notations, magazines, photographs, records, books, you name it and it is there. I could not have done it if the lockdown and the pandemic had not happened as no film-making was happening at all. On the one hand, it gave me something to do and on the other, it was something crying to be done,” says Sandip with a smile.

It has rained in this hot summer afternoon and the drizzle has left puddles in the compound so the air is a bit cool which spills into the room, filling the ambience with warmth. We sit down in the spacious drawing room filled with books all around us. Soon, tea arrives in a beautiful, bone china tea service, a rare scene in our fast-changing world of come, shoot, and please leave.

The Rays are completely rooted to Bengali culture. The door is always attended to by a family member who welcomes you to a spacious drawing room spilling over with books, books and photographs. The corridor is lined on one side with a plethora of plotted plants and the other side has framed black-and-white photographs of Rabindranath Tagore, Ray’s father Sukumar Roy and his mother Suprabha Ray. The other photographs are clear but Suprabha Devi’s portrait is fading every passing day.

Father as “Father”

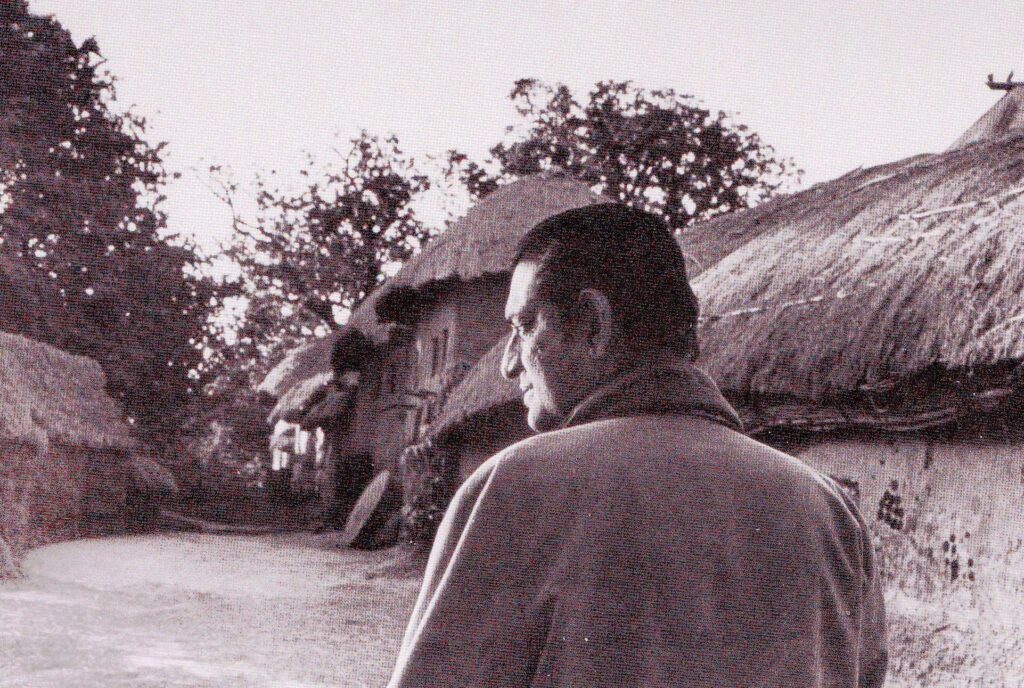

“I was a two-year-old toddler when Baba went to shoot Pather Panchali on location in a village called Boral. My memory is blurred and faint. I remember my mother or my grandmother carrying me in their arms in the shooting site. The only memory I still carry with me is that from the main entrance of Apu’s “home”, I could glimpse a railway line. It was fascinating,” he recounts.

“To me, father was just “father” as I was just too small to understand what he was and what he did. It was only when his pictures began to appear in magazines and newspapers after Pather Panchali became famous across the world that I began to sense that he was something more than just my father. I found that he was different from other fathers because of the many letters he received from abroad and the beautiful postage stamps would fascinate me. Then, I was surprised to see a flurry of white-skinned guests walking in and out of our home all the time. It was something new for me. It gave me a feeling that perhaps my father was someone important,” he says smiling.

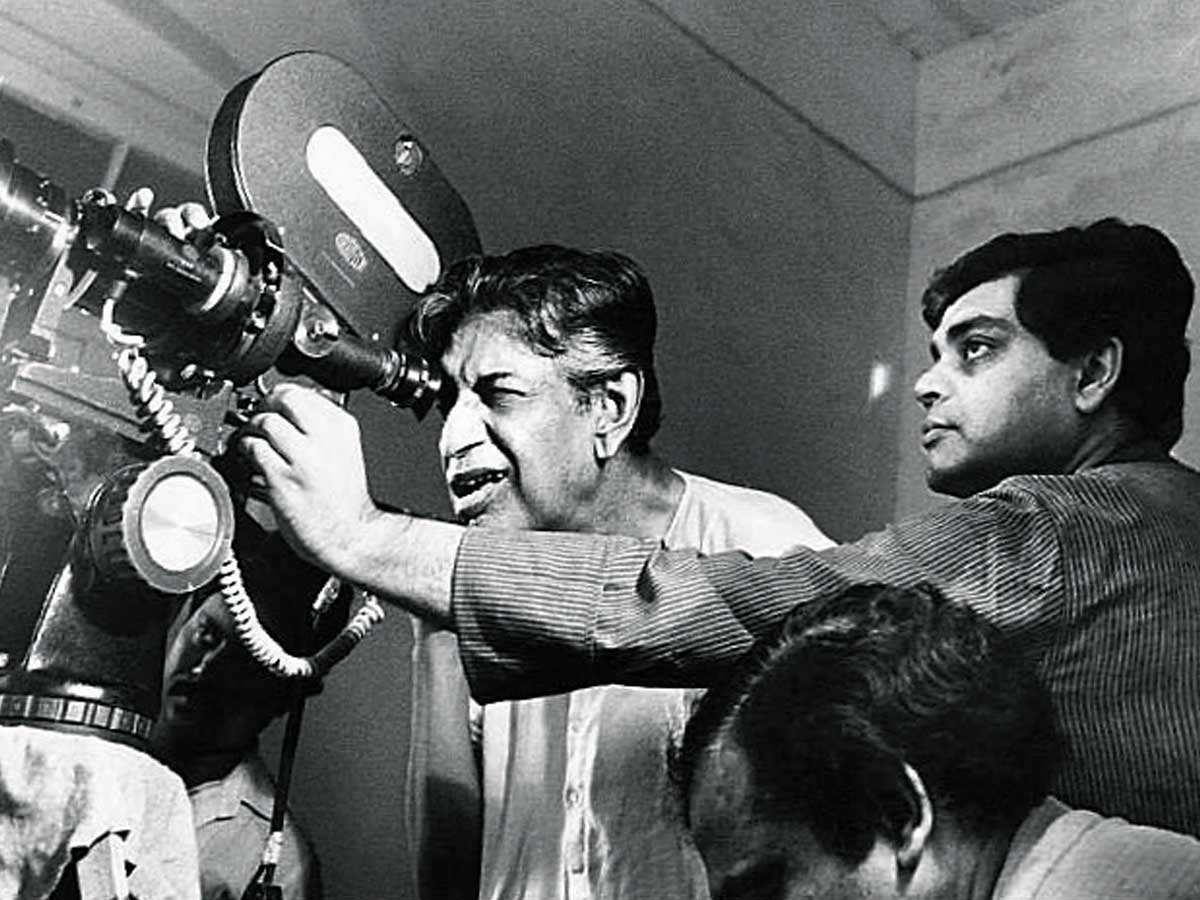

“Another strong memory is the party scene father shot for Parash Pathar where every big star of Bengali cinema featured as guest artists. I did not know nor was I interested in the actors or in the party scene. What pulled me was the camera placed high on a crane where my father sat with the cinematographer Subrata Mitra and the crane went up and down, up and down many times and I wondered how it was done. So, having been brought up literally within an ambience of film-making directly, it never ever occurred to me to practice any vocation other than making films,” he smiles. Since his father would be totally focused on the shoot, Sandip was befriended and taken care of by the members of every film team and literally grew up with them though they were much older than he was. He developed an interest in photography which brought him in closer proximity with his father when the latter was right into filmmaking.

“Baba was such a rooted family man that he would go on location with all of us – my mother, my grandmother, one maternal aunt and me. He organised the shoots to coincide with my school vacations in summer, Durga Pooja and winter. The shootings I missed because they clashed with my exams I will regret forever. One film I missed out the shooting of was Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne and I could not go to Rajasthan where the climax was shot as I had my exams. My mother remained beside me because she was in charge of punishing me, taking care of my studies, my diet and everything else so I do not recall ever being scolded by my father. The other location shoot I missed out on was Aranyer Din Ratri shot in Daltongunje as my exams were round the corner. But one location trip I truly enjoyed was the recce trip we had in the the deserts of Rajasthan—to Jaisalmer, where we went location hunting for Sonar Kella much before it was opened to tourists. When we went there for the first time, a railway line was just being laid and there were no hotels either. But it was great fun and in fact, all these recce tours were fun tours for me.”

By this time, Sandip had become the still photographer for the unit and the film his father was working on. “I began the work from the time he did Pratidwandi and I thoroughly enjoyed clicking the production stills that included my father as he worked. My father had bought me a still camera from Japan, the same model Kurosawa used but for this film, my name did not appear in the credits of the film. That made me sad but also happy because I was really doing something along with my father. I became the official still photographer for Pratidwandi and I was thrilled to see my name in the credits alongside the name of Nemai Ghosh.”

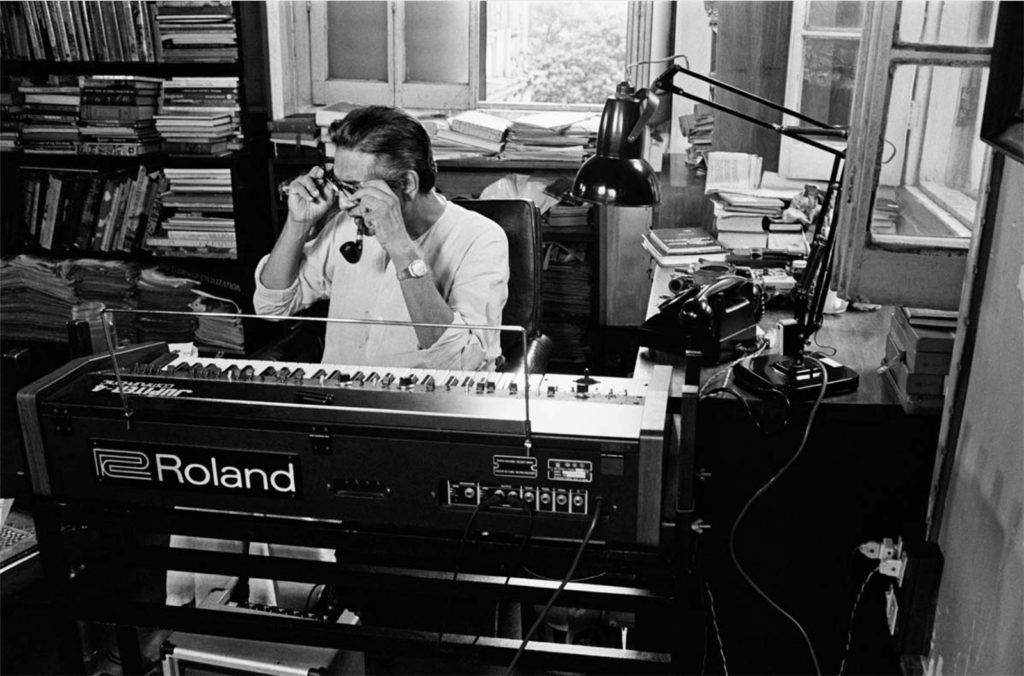

“For Bala, the documentary Baba made on Balasaraswati, the iconic and legendary dancer, I got the opportunity to assist him and by then, I had begun to be very interested in editing and in background music specially after Baba began to write and compose the music for his films himself. Watching a scene I had actually seen being shot now being clipped during editing was magical for me. I also handled the still camera for the film. Years later, I was DOP for his last three feature films – Ganashatru (An Enemy of the People, 1989), Shakha Proshakha (The Branches of the Tree, 1990) and Agantuk (The Stranger, 1991).

The Father – According to the Son

Talking about the subtle influence his father had on him, Sandip says, “As a little boy, I would copy his way of pictorial script writing. His homework was solid and his time-management was incredible. He divided the day into different compartments. He would wake up at around 7.30 in the morning – personal and professional letters – he never kept any letter unanswered and wrote them out in his own hand. Then he would sit down to work on illustrations which he loved to do in natural light, followed by lunch and then writing commissioned features and articles while listening to Western classical music which was his favourite.”

Within this routine, one phase was entirely devoted to family-time and one to adda-time. Lunch and dinner had to be with the entire family and he always insisted on spending family time a lot except, of course, when he was on location. We would chat about everything you could think of and rarely discuss films. He was very fond of food, but simple food cooked at home, nothing elaborate or decorative or complex. He was not particularly fond of fish unless it was Ilish cooked in mustard paste in mustard oil with green chillies. But when he fell ill, he had to give up all his favourite items of food – fish, red meat, luchi and aloo dum. It made him sad but he bore with it.

He was also very fond of his adda sessions on weekends of course, when he was not shooting. He was a great raconteur and had a fascinating sense of humour and satire. He loved these chats and everyone who was anyone would drop in such as Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Shyam Benegal who even made a documentary on Baba and his friends from other fields such as the famous poet Subhash Mukhopadhyay. This would happen between nine in the morning and go on till 12-30 to 1.00 and would dissolve before lunch.

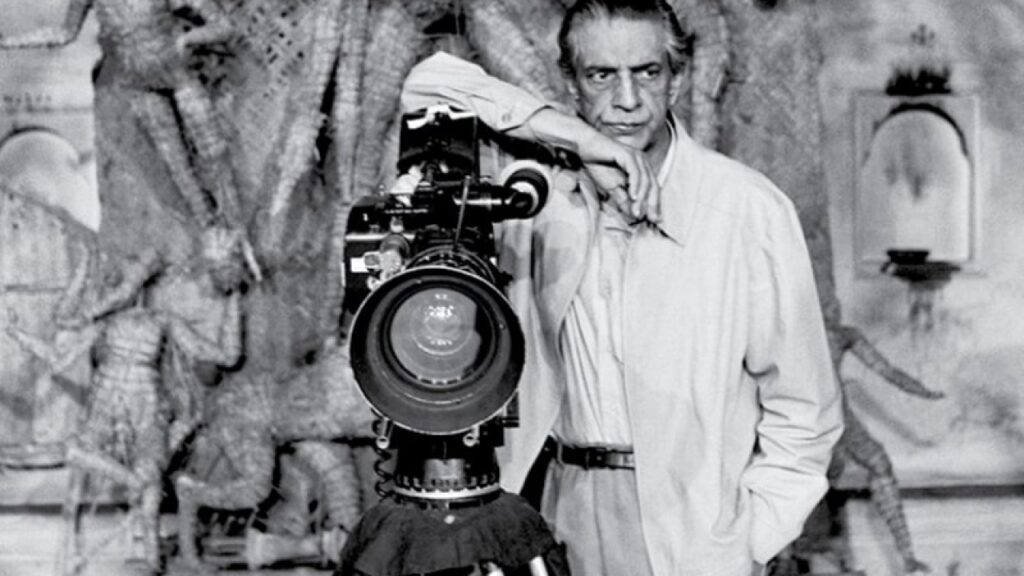

Remembering his father as filmmaker, Sandip says, “As a filmmaker, there was a certain ruthlessness about him. Sometimes, he would spend days working hard to put a scene together. But on the editing table, if he found that that scene was not taking the story forward, he would chop off the entire roll, not caring about how difficult it had been to put it together. The film had to be compact and every scene had to take the story forward. There were other things I learnt from him such as grammar and technique. I started by being a still photographer, and observing him helped me a lot, from exposure to the composition of frames. When I got interested in the technicalities of moviemaking, Baba and his unit members would patiently explain every aspect that befuddled me.”

“I was amazed at the way he kept his cool in every kind of situation. He never, ever lost his temper and he said that he imbibed this from his training in Santiniketan under the painter Nandalal Bose. I knew there were many things which might have irritated him, for film-making is full of built-in tensions, specially for a person as much a perfectionist as he was, but even if he might have been simmering inside, he chose not to express it.”

“I have not known of any other director anywhere working as hard as my Baba did,” says Sandip “After choosing the subject, he would write the script. Actors and actresses would also be chosen by him. He would then ask the main artistes to come to our home and read out the script to them, acting out each role meticulously. In those days, Xerox did not exist. There were no computers or scanners or printers. So, the screenplay would first be handwritten, then copied and carbon-copied by different members of the crew, including myself, then given to the technical crew and the acting cast. It was monumental but my father never looked either disturbed or tired or bored,” he says. “It was very painstaking but we did not know that then. Baba would insist that no member of the acting cast should memorise a single line of dialogue. He could change the dialogue at the last minute and if an actor had memorised his lines, it could become problematic if there was a change at the last minute.”

“When the script was finalised, he would hand the master copy, a foolscap-sheeted copy bound with red cloth famously known as his kheror khata to my mother, with a pencil and eraser and she would incorporate corrections which, if my father felt were right, would put them and then the script-reading sessions would happen where actors could offer their own suggestions as my father was never rigid, never,” Sandip informs.

“Next, he would go out to buy dress material for the men while my mother and I would help him to buy saris for the female artists. Make-up tests would be held at our house. He would draw out each character, how he wanted their hair and make-up to be done. Both the art director and the cameraman found it easy to work with him,” he adds. “I was given the same responsibility for Hirak Rajar Deshe.

The Father as a Writer

“When my father was a student at Kala Bhavan in Santiniketan, he had written two short stories. After all, writing ran in his blood what with his grandfather Upendra Kishore Roy Choudhury and father Sukumar Ray being renowned authors. But those two short stories ended his affair with creative writing. But then, his close friend poet Subhash Mukhopadhyay persuaded him to revive the children’s magazine Sandesh, first founded by my great-grandfather and then revived by my grandfather Sukumar Ray. Baba agreed and he, along with Subhash Mukhopadhyay, revived Sandesh in 1961 and the two friends edited it jointly. They edited the magazine jointly and it soon became extremely popular among children.” Sandesh is now edited by Sandip himself.

“Baba felt that as an editor, he also had to contribute to the creative content so he began translating the limericks of Edward Lear and the writings of Louis Carroll. But they were not his original creations so he created Professor Shanku, the mad scientist, now a literary icon, for the special Pooja Number of Sandesh in 1961. He created strange ideas for stories without stopping. Then, in 1965, the famous Feluda, the detective many say has similarities with my father, was born and became one of the most outstanding and memorable detective characters in Bengali literature. He did the illustrations himself and this added t the USP of his writings.

“I have myself made several feature films and television serials revolving around the adventures of Feluda who was an action-oriented, very intellectual detective. But looking back, the whole story of the resurrection of Sandesh worked like a trigger for my father’s very successful career as a creative writer. But for Sandesh, Baba might never have switched on his writing pen, apart of course, from his film scripts and his innumerable features, articles and essays on films he wrote on the request of editors from various magazines. Volumes of Feluda’s adventures remain on the top selling list till today among children and teenagers of West Bengal.”

Sandip goes on to inform that young director Sagnik Chatterjee made a wonderful documentary called Feluda – 50 Years of Ray’s Detective essaying different aspects of Feluda which sheds considerable light on Ray’s literary talents. In 2017, Feluda turned 50.

Father, Son and Filmmaking

“My first directorial film Phatik Chand (1983) received an award in the International Children’s Film Festival in Vancouver. It was based on my father’s story. Baba did not look at my script at all. He would watch my film only after the first cut and then he would write the music for my film. He was ruthless and told me that its footage was too long. He said, “Your film according to the first cut is two hours twenty minutes long. You must cut it down to 1:40 minutes,” but he did not help me to actually implement this. Only after I had cut it down did he agree to write the music. He would insist never to be lax in editing,” says Sandip who has made altogether 28 films and television serials, many of them based on his father’s stories.

His regret is that when his second feature film Goopy Bagha Phire Elo (1992) became a thumping box office hit, his father had just passed away. In an interview to a magazine about what he felt about his son as a filmmaker, Satyajit Ray has gone on record say, “Sandip was the best assistant (director) I have ever had.” Ray went on, “Sandip is handicapped by the additional weight of being my son. His latest work – The Return of Goopy & Bagha is hundred percent his own work. Only the plot and a few songs were mine. But the direction, the photography, the script were all Sandip’s. In his handling of the camera, he is a master. His skill is better than mine. The bravura work of his cinematography is incomparable.”

Sandip elaborates that he subconsciously imbibed his father’s economical way of working, the intensive homework he put in not only in a film but in every frame, every scene, every character of the film and that as a filmmaker, “I had to be absolutely ruthless about my work. He loved the double-headed technique I had used in Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne. When I screened the first cut of the film for him, I asked the projectionist to put in an interval so that he could comment on what had gone by. But he got so irritated with the interval that he told the projectionist to keep the film rolling. That told me that he loved the film” reminisces Sandip adding that his unit members were warm and helpful. He said that his father was a very good observer.

Of Father and Son

Does Sandip ever feel the pressure of being the son of one of the most outstanding filmmakers in the world? Or does he look upon this as an asset? Sandip says, “I have never even thought about this being a burden or as asset. It has never been a burden for me. I consider myself extremely fortunate to have had such a loving father and a unique friend, philosopher and guide who inspires me till this day. Had I felt this to be a burden, life would have been claustrophobic. I enjoy basking in the glory of having been born into a family where genius and talent run down the line, hand in hand.” And we let him have the last word.