This issue is about the movies of the 1970s that changed movie-watching in India. I choose to write on Siddhartha which to me, was a lovely soft porn movie. An adaption of a novel by Hermann Hesse, Conrad Rooks wrote, directed and produced the film and in some respects captured the spirit of the novel. Though some of my favourite scenes from the book are missing, Siddhartha contemplating suicide, sleeping and walking to the river only to find Govinda watching over him. This notwithstanding, it is an elegantly produced adaption of a Hermann classic, writes Vickram Sethi

The Nobel prizewinner Hermann Hesse wrote a novel called Siddhartha in 1922. It’s a novel about Indian spirituality and is one of the few successful examples of Indian philosophy presented by a Western author. Almost every Indian who has sat through the countless sermons that are delivered every hour on Indian philosophical thought hears the questions: Who am I? Where did I come from? Where I am going? What is my purpose?

This story is of Siddhartha, a rich son, searching for the meaning of life. The film conveys Siddhartha’s journey on the path of self-knowledge. It is a simplification of a simplification. A spiritual quest most every Indian hears again and again all throughout their lives.

Conrad Rooks made the novel into a movie in 1972. The movie, in some ways, is better than the book as it gives the viewer more imagination about the representation of the agony of looking for the meaning of life. In 1972, the movie was release in Mumbai at the Liberty cinema. Indian movie critics then thought the story was pointless. Siddhartha’s search for immortality, honesty or whatever he leaves homes to find, doesn’t exist and it isn’t worth finding. His character matches that of many such protagonists in Indian folklore. One problem with this kind of story is that the Indian audience already knows that he is chasing a rainbow and that they have all heard these platitudes again and again. It’s an old fairy tale about the pointless quest. However, to the west, this quest for knowledge is an important question that needs a satisfactory answer.

The photography is gorgeous and the gentle editing lulls us into accepting the fairy tale. The beauty of the movie is in the misty panoramas of the quiet river. The beauty of the landscapes is not only the superficial one of picture post cards, but a philosophical one as well. One that tells you that a beautiful world is essentially a good, complete, happy world. A world in which you can afford the completely focus on your personal search for meaning and spirituality. The photography captures both the exotic beauty and the poverty of a landscapes that could have been India many centuries ago.

The music of the film composed by Hemant Kumar works beautifully. Very simple melodies, mostly Bengali that are haunting and work very well with the river and nature, depicted in the film. O re nadi is my favourite. In many of the scenes, the synergy of the photography and the music is superb. When the film got released, a few Bengali movie critics lamented that the photography as not even remotely as real as Satyajit Ray’s Appu trilogy and even the Bengali songs were not up to the mark. One of them remarked that the Buddha was born in Nepal. At that time, many felt the pace of the film was slow and was laced with pavement philosophy like that in a high school play. Critics are critics and sometimes they write for themselves.

The story of Siddhartha is part of Indian folklore. Two friends, Siddharth and Govind set out to find the meaning of life one of them parts ways and follows the Buddha, Siddhartha wanders off on his own. The point is if you must pursue your quest you have to do it of your own. The words “who am I” and “where I am going” seemed irrelevant to me when I saw the movie in 1972. Then the words “I can think”, “I can wait” and “I can play” were more resounding. Now, 50 years later, the words suddenly seemed to have more meaning. The message that Siddhartha conveys to Govinda at the end of the movie is the boatman wisdom: “Live in the present. Stop seeking. Don’t worry, be happy.

It is the ultimate soul-searching advice, everything changes, everything return stop searching, stop worrying gives love. Such deep Indian philosophy presented by non- Indians I find amazing. It’s a thought that will stay with you for long, may be a life time.

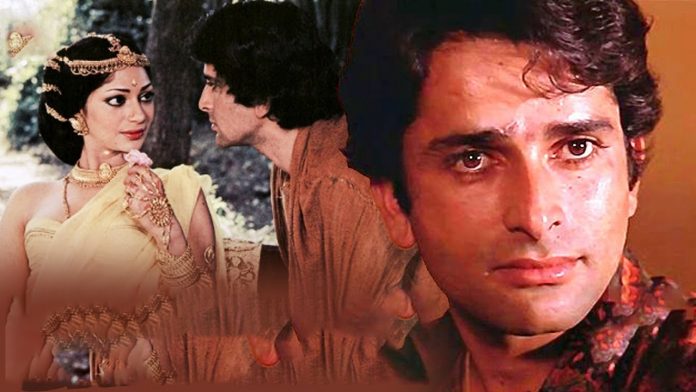

The erotic encounters between Siddhartha, played by the handsome Shashi Kapoor and Kamla played by Simi Garewal were badly censored in India. Their so called the first time was painful devoid of any passion that Kamla is supposed to generate.

I was lucky to see the movie in London. The courtesan Kamla is a gorgeous creature whose lovely eyes, long aristocratic nose, pouty lips, ebony skin and a super sexy figure is what Indian beauty is all about. Never mind about the more profound philosophies of “who am I” or “why am I here”. A courtesan like Kamla can help in settling some of these troublesome issues.